A version of this article appeared in the October 2010 issue of Informer: The History of American Crime and Law Enforcement. It is a revision of an article that first appeared on this website in 2002.

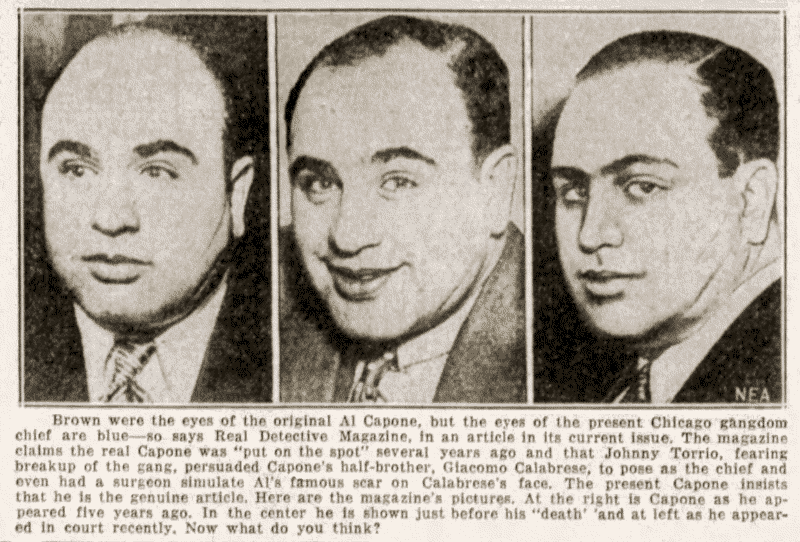

Capone mugshots compared

Al Capone's ten-month imprisonment in Philadelphia gave rise to a number of conspiracy theories. The most complex theory was advanced by Real Detective magazine in 1931. That periodical charged that the real Al Capone was dead and the man who had served time for carrying a deadly weapon in Philadelphia was an imposter.

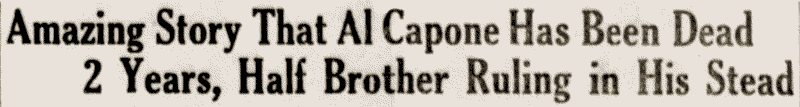

Al Capone

Real Detective charged that, at the time of his imprisonment, Capone's eye color changed from brown to blue, his ears grew rounder, and both his famous facial scar and his fingerprints changed noticeably.

The magazine asserted that the real Capone had been murdered - put "on the spot" on orders from Johnny Torrio, former Chicago gang boss and (according to Real Detective) unrivaled master of the Italian American underworld. The killing supposedly took place outside Atlantic City in May 1929.

To provide cover for the killing and to hold Capone's Chicago gang together, Torrio located a Capone illegitimate half-brother in Naples. He smuggled the man, reportedly named Giacomo Calabrese, into the United States. Torrio then arranged to have Calabrese locked away in Philadelphia with Capone's old bodyguard Frankie Rio (who must have cooperated in the conspiracy), so Rio could help the imposter learn the real Capone's history and characteristics.

Newspapers across the country helped to circulate the story, some picking it up from Bill Biesel's column for the NEA Chicago Bureau. Photographs were run to show the reported differences between the "real" Capone's facial scar and the one said to have been surgically inflicted on his replacement.

Jake Lingle

Real Detective magazine noted that the jailed Capone lookalike refused prison visits from a number of Capone family members, who would have recognized him as a fake. It argued further that, when the man was released in spring of 1930, he avoided contact with Capone's old friend, Chicago journalist Jake Lingle. Lingle's ability to blow the whistle on the phony Capone ended abruptly - along with his life - when he was shot in the back of the head later that year.

Though Real Detective publisher J.M. Lansinger insisted that his magazine's facts had been authenticated, many found the story baseless and silly. Still, it caught the eye of an important law enforcement official in Washington, D.C.

Real Detective followed up its sensational imposter story a few months later with an article indicating that records of the United States War Department confirmed the death of Al Capone. It said the War Department had records on Capone from the time he entered World War I-era military service under the name "Alfonso Copone."

In August, U.S. Bureau of Investigation (after 1935, the BOI was renamed "Federal Bureau of Investigation") Director John Edgar Hoover felt the matter was important enough for a Bureau investigation. He ordered L.B. Reed of the Washington office to check into the War Department records. A week later, he ordered W.A. McSwain, special agent in charge of the Chicago office, to compare Capone arrest data from the Chicago and Philadelphia police departments.

Torrio

McSwain responded on August 20. Fingerprints taken as Capone was transferred to Pennsylvania's Eastern State Penitentiary in August 1929 had been compared with those taken by Chicago police after the shooting of Johnny Torrio in 1925. The prints were determined to be identical.

On the twenty-fifth, Reed sent the results of his investigation to Hoover. Reed learned that gang boss Al Capone was not the same person as the "Alfonso Copone" of the Army: "No one served in the World War under the name of Alphonse Capone, nor did any individual serve in the World War whose fingerprints are identical with those of the Alphonse Capone about whom the Bureau is concerned."

Reed further discovered that the fingerprints on file in Pennsylvania were an identical match for prints taken in New York late in 1925, when Capone and three other men were arrested for possession of a firearm.

Reed wrote, "It is believed that the foregoing information is sufficient to establish that the article referred to in the magazine Real Detective is without foundation."

When news reporters asked Capone about the Real Detective allegation, he called the story "a lot of apple sauce." The gang boss added, "I ain't dead, but it's all right for 'em to think so if they want to."