This article was written in 2006. It was first published in the December 2006 issue of the On the Spot Journal. A great deal of additional information was uncovered following publication. For a complete telling of the Sberna story, see the book, Wrongly Executed?.

Patrolman John H. A. Wilson, an eleven-year member of the New York Police Department, was on strike-duty in front of the E. J. Barry drug warehouse at 54 Fulton Street in lower Manhattan. Employees of the warehouse had walked off the job, and Wilson was sent to ensure picketers behaved themselves.

Old Slip Station exterior and interior

It was an odd assignment for him. He usually worked behind a desk at the First Precinct's Old Slip Station[1], issuing applications for pistol permits in the financial district. But a number of regular patrolmen had been drawn away to keep order and move traffic around a large American Legion convention downtown, and Wilson was temporarily pulled from his desk.[2]

At about ten forty on Thursday morning, September 23, 1937, Wilson heard a man yelling, "Police!" He gazed across the street to the Rudisch Refining Company at 65 Fulton. Up on the fourth floor, a gray-haired man leaned from a window and shouted, "Holdup on the second floor. There's three men. They've all got guns."

The Rudisch building, sitting between Gold and Cliff Streets just a few blocks from the South Street Seaport and the Brooklyn Bridge,[3] was a processing plant for precious metals. It was known for its work with gold.

As a career paper-pusher, thirty-seven-year-old Wilson was an unlikely hero. But he was a dedicated public servant and a second-generation cop. (His father was Lieutenant George Wilson, retired from the force in 1925.) Wilson charged alone across the street and into the Rudisch plant. He rushed up dark stairs and burst through the metal door to the second floor offices.

Three gunmen were in control of the offices. A short time earlier they had passed through the main entrance, scaled over the metal grills that blocked the stairway and pushed their way into the administrative quarters with pistols drawn.

On their way in, the would-be robbers failed to notice elderly Max Satz, concealed by a stack of cartons. After they passed, Satz, father-in-law of plant owner Louis Rudisch, climbed a rear fire escape to the fourth floor to shout for help.

Handing his pistol to an accomplice, one of the intruders quickly bound Louis Rudisch and employee Abraham Kever with wire. He then tied up employees Louis Wolk and Morris Reich. As he began binding porter Rudy Wyatt, the metal door swung open.

Stationed by the door, one of the gunman saw Patrolman Wilson enter from the dark stairway. He planted his pistol butt into Wilson's head. The officer sprawled on the floor. Dazed but still conscious, he fired his handgun. Fire was returned. The intruder with two weapons fired an estimated ten shots at Wilson, emptying one pistol and nearly emptying the other.[4]

During the shootout, the gunman closest to the door struggled with Wilson and bumped into a pot of melted wax,[5] spilling it on the left side of his jacket and his left hand and on Wilson's right hand.[6] Burned, Wilson let go of his revolver. The gunman reached for it but was also scalded by the hot wax.

The three gunmen scrapped their robbery plans and fled the building. Two of the men ran toward Gold Street. The other turned toward Cliff Street.[7] The men left behind one .38 caliber handgun and a jacket soaked with wax.[8]

The noise of the incident attracted the attention of other workers at the plant. They rushed to the second floor offices to find Patrolman Wilson struggling to get to his feet. The officer then fell to the floor and lost consciousness.

Officer Wilson

Wilson was taken a short distance to Beekman Street Hospital.[9] Doctors tended as best they could to his wounds. Four officers -- William Higgins, William LaForge, George J. Neilson and William Zimmerman -- each gave a pint of blood, hoping to help their comrade. Six other officers stood ready to do the same. Police Commissioner Lewis J. Valentine waited beside Wilson's bed in case the patrolman gave some clue as to the identities of his attackers.[10]

Wilson never regained consciousness. He succumbed to his injuries at five forty five in the afternoon. He was survived by his wife Anna[11] and three daughters, ranging in age from three to thirteen.

The New York Police Department gave Wilson an inspector's funeral. Hundreds attended a September 26 wake held at the Prospect Place, Staten Island, home of his sister, Mrs. Charles Shay.[12] Commissioner Valentine was present as Wilson was laid to rest the following day.[13] The department also honored him in a 1938 ceremony for officers killed in the line of duty.[14]

The three gunmen had left just enough evidence behind to delight police investigators. One day after the shooting, Commissioner Valentine told the press that detectives were "working on something that looks very good."[15]

Less than two weeks later, the department claimed to have arrested two of the three cop-killers. The suspects were identified as Charles Sberna,[16] alias Frank Costeri, twenty seven, of 337 East 106th Street, and Salvatore Gati (also written Gatti and Gotti), aliases Frank Gallo and Frank Costa, twenty seven, of 1683 Lexington Avenue.

Both men had police records and were on parole from Sing Sing. They had been arrested and discharged three times each.[17] They both had been implicated in a payroll robbery ($461) near Seventeenth Street and Union Square.[18] They were finally jailed after pleading guilty to committing second degree assault in a taxi. They were paroled in September 1936.[19]

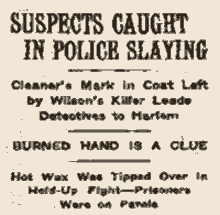

NY Times

While the New York press delighted in reporting on Sberna's parole and earlier criminal activities, it seemed to pay little attention to his family ties to the underworld. Sberna had married Carmela Morello, daughter of Giuseppe Morello, who had served as the American Mafia's boss of bosses.[20] Morello spent a lengthy term in Atlanta Federal Prison for counterfeiting and was later assassinated in his Manhattan offices at the start of the underworld's Castellamarese War in 1930. [21]

Detectives had been led to Sberna and Gati by an East Harlem cleaner's mark left in the discarded and wax-covered jacket. Questioning in the neighborhood revealed that a man with a bandaged hand had been seen there. Witnesses examined a "rogues gallery" and singled out Gati. Police went to Gati's and Sberna's homes but learned that the men had been away since two days after Wilson's killing.

On the afternoon of October 5, police caught up with Gati and Sberna at Worth and Centre Streets, as they made a routine visit to their parole officers.[22] The two men were placed under arrest and brought into the West Twentieth Street Police Station. There, they were questioned by detectives and Assistant District Attorneys Sylvester Cosentino and Louis Capazzoli.[23]

Gati had an obvious burn wound on his hand and initially could not explain how it got there. Later he decided that an accident occurred while making candy at home.[24]

Gati had more trouble explaining how his fingerprint, perfectly preserved in wax, ended up on Patrolman Wilson's revolver.

Gati and Sberna denied any knowledge of the Wilson killing or the attempt to rob the Rudisch company. Sberna claimed he had been at home with an ear problem on September 23, but he faltered and could not easily remember what he had been doing on other days.

An interesting point of law was raised as Sberna and Gati awaited trial on the capital crime of killing a police officer. Gati's attorneys, Samuel S.Leibowitz and Vincent Impelletteri, argued on February 25, 1938, that the defense should have the right to bring in its own fingerprint expert to examine the print on Patrolman Wilson's weapon.

Assistant District Attorney Jacob J. Rosenblum opposed the motion. At the time, there was no New York statute allowing a criminal defendant access to prosecution evidence before trial.

Judge John J. Freschi denied the defense motion but, in a sixteen-page decision, urged that the state legislature address the issue. He noted that "discovery and inspection before trial" was already a guaranteed right in civil suits.

"Our main objective should be plain justice for all...," Judge Freschi wrote. "At no time should the prosecution be forced so as to invade and prejudice the conserved rights of the people, or denials decreed that work irreparable injustice to the accused. There is no more important preliminary matter than a defendant's preparation for trial." [25]

Attorney Leibowitz was widely regarded as the "new Clarence Darrow." A Romanian-Jewish immigrant, he had put together an impressive record in capital punishment cases. According to his count, none of his clients had ever gone to the chair.[26]

Sberna also boasted an eminent legal mind as his counsel. Caesar B. F. Barra, an immigrant from Salerno, Italy, [27] handled his case. Barra, the Bruce Cutler of his day, was a very highly regarded defense attorney, particularly among organized criminals. His firm represented a number of notorious outlaws, including Charlie "Lucky" Luciano and Johnny "The Fox" Torrio.[28]

Before the trial began, Leibowitz attempted to shift the responsibility of the case to an associate. Judge James G. Wallace discussed the matter with Gati, who insisted that he had paid for Leibowitz to represent him and wanted Leibowitz to do so personally. Judge Wallace ordered Leibowitz to remain on the case.[29]

Leibowitz's behavior in this matter is questionable. While it is possible he sensed that his record in capital cases was in danger, it seems as likely that he was suffering from exhaustion. The recently resolved "Scottsboro Boys" case had been physically and intellectually demanding and probably demoralizing for the forty-five-year-old attorney.[30]

At trial, Assistant D.A. Rosenblum charged that Sberna, Gati and their unknown accomplice had been aware of Louis Rudisch's recent purchase of a quantity of platinum valued at up to $12,000. It was that platinum, said Rosenblum, that the gunmen sought when they entered the Fulton Street plant.

'Old Sparky'

Of course, an unanswered question was: How did the the criminals become aware of the purchase? The press suggested that they were hirelings of some underworld mastermind either related to the platinum supplier or in some way privy to the transaction.[31]

The robbery was foiled, Rosenblum argued, simply because Rudisch did not immediately bring the platinum to the plant after its purchase.

Sberna was said to be the man who bound the office workers with wire. No witnesses indicated that he had fired a weapon at Patrolman Wilson or even that he had been in possession of a pistol at the time Wilson entered the office. Under the law, that distinction made little difference, as Wilson's death was the result of the criminal act in which the three men were engaged.

However, there was also some suggestion that Sberna was not part of the attempted robbery at all. The prosecution witnesses who seemed most positive of Sberna's identity were those who claimed to have seen a man who looked like him rushing from the scene.[32]

According to some sources, the law itself was aware of Sberna's innocence.

Gati allegedly had a private pretrial conversation with a commander in the Homicide Bureau. In that conversation, he admitted his own guilt in Wilson's slaying and insisted that Sberna was innocent. The commander reportedly offered to have Sberna released if Gati would name his actual accomplices. Sberna refused to cooperate and the case went ahead.[33]

On June 29, 1938, a jury returned with a verdict of guilty against Gati and Sberna. The panel had deliberated for more than seventeen hours, bringing in the verdict at five fifteen in the morning.

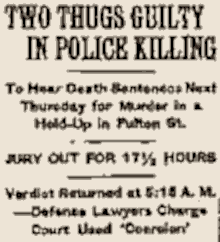

NY Times

The final three hours of jury deliberations were reportedly focused on whether to recommend mercy for either or both of the defendants, which would have ruled out capital punishment and mandated a life prison sentence. In the end, the panel decided against a mercy recommendation.

Attorney Barra, who had gone home to Bath Beach, Brooklyn, at three in the morning, had to be rushed back to the courtroom by police squad car to hear the verdict.

The defense attorneys protested the lack of a mercy recommendation, feeling that the judge had improperly directed the jury away from that course.[34]

A mandatory sentence of death by electrocution was formally announced on July 7. The two convicted cop-killers stood and listened to the sentence without any show of emotion.[35]

Deputies took Gati and Sberna by van from the Tombs lockup to Grand Central Station and brought them by train to Sing Sing prison. The two men spent the next six months on death row.

The convictions were upheld by the Court of Appeals in Albany, NY, on November 22. With the capital punishment of the two men imminent, the New York Times noted the incompleteness of the case:

A confederate of Gati and Sberna in the slaying of Patrolman John H. A. Wilson, in the hold-up of a gold and platinum refining concern at 65 Fulton Street on Sept. 23, 1937, never was captured. Nor were the police able to learn from Gati and Sberna the identity of the 'fingerman' who had sent them to rob the place.[36]

Early in the day, January 5, 1939, Sberna was visited by his wife, and Gati was visited by his mother. Each prisoner reportedly held out hope of executive clemency until finally strapped into "Old Sparky" that evening.

Gati and Sberna, both twenty nine years old, were put to death in Sing Sing's electric chair.[37]

Following the executions, there were widespread murmurs about an innocent man having been sent to the chair.

Some said that Sing Sing Warden Lewis E. Lawes spoke about Sberna's innocence on the eve of the execution. "For the first time," Lawes was supposed to have said to a newspaper reporter, "I think we may be sending an innocent man to the chair. I've done all I can to save him, but nobody believes me." [38]

Sgt. Kilpatrick

Others attributed a similar quote to the prison chaplain, who reportedly made 15 visits to the district attorney's office to plead for Sberna's life.[39] Father John P. McCaffrey, the Roman Catholic chaplain, is believed to have said, "This is the first time I've ever been positive that an innocent man was going to the chair."[40]

Louder objections were heard when Nunzio Romano, age thirty, was arrested in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, in the summer of 1939.[41] Some witnesses who identified Sberna as one of Gati's accomplices reportedly decided that Romano was actually the man they saw.

Romano was wanted for questioning on both the Wilson killing and the slaying of police Sgt. David Kilpatrick, fifty seven, during a January 28, 1938, holdup of a Bronx pawnshop. Two other men were connected with that crime. One, George DeRenna, was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. The other was killed in a shootout with police. Investigators had been tracking Romano for a year through New York, New Jersey, New England and Pennsylvania.

The New York Daily Mirror's syndicated columnist, Walter Winchell, began labeling the Sberna execution a mistake in late August 1939. He noted that the imprisoned DeRenna and Romano had worked as a team. If Romano had participated in the attempted robbery at the Rudisch company, it seemed reasonable that DeRenna was also there. Winchell, therefore, was able to account for all three Rudisch robbers without counting Sberna.

Winchell

"For the first time in New York history," he wrote, "there is practically a certainty that an innocent man was executed in the electric chair at Sing Sing... Two men were tried for it last winter, and a third is in Auburn [Prison]. Now, with the arrest the other day of Nunzio Romano in Penn., it looks as though one of the lads... was juiced by mistake - because witnesses tell police Romano is the guy."[42]

Warden Lawes made his feelings known in a book, "Meet the Murderer," published in 1940. Using fictitious names, he referred unmistakably to the Sberna matter, describing the efforts made by the chaplain and himself to save Sberna's life.[43]

Winchell reserved for a series of columns in spring of 1942 his most severe attacks against prosecutors and police officers he perceived as being more concerned with their own reputations than with justice:

Now, the plot sickens... By this time, when witnesses of the first case [Wilson's killing] took a look at [Romano], they realized he was really Gati's accomplice... But the other kid [Sberna] was beyond saving - and so the law had to free the accomplice - without even trying him for [Sgt. Kilpatrick's] murder... To do so would air the whole blunder... And they couldn't try him for the first murder - for which another man had already been put to death.[44]

Winchell also revealed a disturbing rumor.

"Sberna's family (and this I cannot prove), according to their intimates - has been staked by a 'sort of hush fund.' And the real killer, now free, is working for a union."[45]

The Sberna execution is frequently cited by opponents of capital punishment as an instance in which an innocent life was erroneously taken by the state. It appears certain that the whole truth of the Wilson killing and Sberna's role in it - if any - will never be known. But it is probably an abuse of the term "innocent" to apply it to Sberna, who by most accounts was a habitual criminal.

Still, the Sberna story haunts us as an example of our own unwillingness to show mercy when mercy is clearly called for. A life prison sentence - the result of a jury's mercy recommendation - would have been appropriate even for the harshest reasonable view of Sberna's actions on September 23, 1937.

And such a sentence would have left open the possibility of correcting a judicial error.

1- The station was located on Old Slip between Front and South Streets.

2- "Policeman Slain in Gold Hold-up" New York Times, Sep. 24, 1937, p. 1.

3- Due to building renumbering 65 Fulton is now closer to the river than it was.

4- "Policeman Slain..."

5- Wax was commonly used in offices as an adhesive and a seal for envelopes and packages. It was also used as a lubricant in the processing of precious metals into wires. Rudisch used molten wax in the design of jewelry molds.

6- "Suspects Caught in Police Slaying," New York Times, Oct. 6, 1937, p. 21.

7- "Policeman Slain..."

8- "Suspects Caught..."

9- Beekman was later incorporated into the New York Downtown Hospital.

10- "Policeman Slain..."

11- "Policeman Slain..." indicates his wife was named Margaret. But the 1930 U.S. Census shows the wife's name was Anna. The couple had a daughter named Margaret.

12- "Honor Slain Policeman," New York Times, Sep. 27, 1937, p. 3.

13- "Death and a Crime Sadden Valentine," New York Times, Sep. 28, 1937, p.48.

14- "5 Slain Policemen Cited for Awards," New York Times, Apr. 25, 1938, p. 18.

15- "Hopeful of 'Break' in Police Slaying," New York Times, Sep. 25, 1937, pg. 6.

16- The name was also written in published reports as "Scherma" and "Sberma."

17- "2 Men Identified in Police Slaying," New York Times, Oct. 7, 1937, p. 56.

18- "Suspects Caught in Police Slaying," New York Times, Oct. 6, 1937, p. 21.

19- "2 Men Identified in Police Slaying," New York Times, Oct. 7, 1937, p. 56.

20- Gentile, Nick. Vita di Capomafia (Rome: Editori Riuniti, 1963), p. 60, 66, 70, 76; Bonanno, Joseph. A Man of Honor. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1983), p. 98-107.

21- Downey, Patrick. Gangster City (Fort Lee, NJ: Barricade, 2004), p. 38-39; Maas, Peter. The Valachi Papers (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1968), p. 87-88.

22- "2 Men Identified..."

23- "Suspects Caught..."

24- "2 Men Identified..."

25- "Need for New Law of Evidence Seen," New York Times, Apr. 24, 1938, p. 9.

26- "Scottsboro Boys," University of Missouri - Kansas City Law School, faculty projects.

27- "Italian ancestry politicians," Political Graveyard, politicalgraveyard.com.

28- Www.iannuzzi.net.

29- "Policeman's Slayers Fail to Win Appeal," New York Times, Nov. 23, 1938, p. 46.

30- Jurist.law.pitt.edu.

31- "Policeman's Slayers..."

32- "Walter Winchell: Man About New York," Charleston WV Daily Mail, Feb. 25, 1942, p. 10.

33- Palimpsest.org.uk.

34- "Two Thugs Guilty in Police Killing," New York Times, Jun. 30, 1938, p. 16.

35- "2 Sentenced to Die in Police Killing," New York Times, Jul. 8, 1938, p. 3.

36- "Policeman's Slayers..."

37- "Three Put to Death in Chair at Sing Sing," New York Times, Jan. 6, 1939, p. 8.

38- "Walter Winchell..."

39- "Walter Winchell: The Man on Broadway," Syracuse NY Herald Journal, Mar. 3, 1942, p. 13.

40- Palimpsest.org.uk.

41- "Suspect in Slayings of Policemen Seized," New York Times, Aug. 4, 1939, p. 3.

42- "Walter Winchell: Man About Town," Nevada State Journal, Aug. 26, 1939, p. 4.

43- Lawes, Lewis. Meet the Murderer! New York: Harper & Brothers, 1940.

44- "Walter Winchell..."

45- "Walter Winchell..."