Editor's note: Following is a 2017 revision of an earlier Edmond Valin article on this website.

- Joseph Bonanno [1]

Bill Bonanno

In 1964, Salvatore “Bill” Bonanno was elected to the position of consigliere in the Bonanno Crime Family. His quick rise within the crime family divided the membership and set off a shooting war that the press dubbed the “Banana War.” The conflict reshaped the New York underworld and took down the last remaining boss of New York’s original Five Families.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation had a front row seat to it all after they developed a secret source at the highest levels of the Bonanno Crime Family hierarchy. That source identified members, shared Mafia Intel, and became the eyes and ears for law enforcement during a tumultuous period in La Cosa Nostra history.

In order to figure out the informant’s identity and determine what motivated him to “talk,” it is necessary to go back to the beginning of the decade when the seeds of the Bonanno bust up were first planted.

Joe Bonanno

For more than thirty years, Joseph Bonanno had led the Bonanno Crime Family. It was one of the most stable LCN crime families in New York City. By staying small and close-knit - a large portion of the early membership came from the same town in Sicily - it avoided the infighting that plagued some of the other crime families. But the unity of the group began to fracture after Joseph Bonanno fell out with the Commission, the decision-making body that regulated LCN activities.

The rift with the Commission started in 1961, after Joseph Bonanno was accused of plotting to kill Los Angeles Crime Family boss Frank DeSimone. The murder was said to be the first step in Bonanno’s scheme to take over organized crime in California and put his son Bill Bonanno in charge. The plot fell apart after someone got cold feet and spilled the beans. Bonanno was somehow able to mend fences with the other LCN bosses, and the plot was “forgotten.” [2] But it did show the ambitions Bonanno had for himself and his son.

Two years later, Joseph Bonanno got caught up in another failed murder plot, when he allegedly conspired with Colombo Crime Family leader Joseph Magliocco to kill New York bosses Carlo Gambino and Thomas Lucchese. The plot would have made Bonanno the most powerful crime boss in the country had it succeeded.

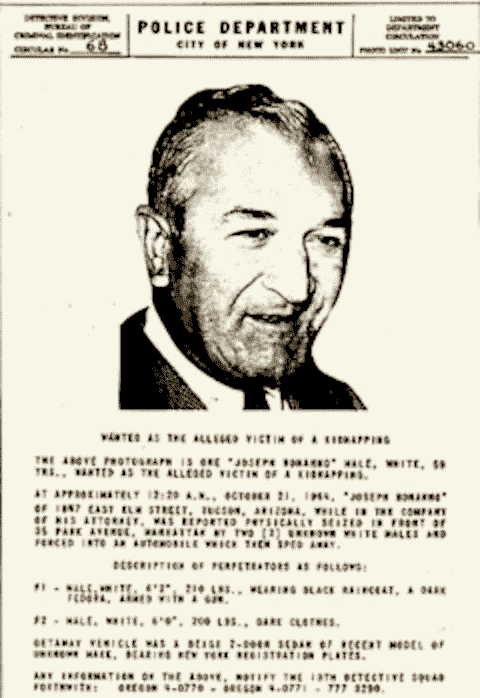

NYPD notice of Bonanno kidnapping

The Commission tried to question Magliocco and Bonanno after details of the plot leaked out. Bonanno denied any involvement but refused to meet. He refused five separate requests to explain his actions. Magliocco met with the Commission and admitted he ordered the hits. Magliocco said he acted alone, but Gambino and Lucchese thought Bonanno was behind it all. [3]

“Whether we call a man a stool pigeon, a snitch, a stoolie, a backstabber, a coward, or a whistleblower, it all means the same thing to us: the mark of disloyalty.”

"But when a man betrays his Family or friends, he betrays himself. Forever after, he is destined to wander aimlessly in the purgatory of the subconscious and the soul, nevermore to find peace or contentment.”

"To the best of my knowledge, there were no major informers among the true followers of our tradition in America.” [25]

Bill Bonanno was elected to the position of consigliere in this hostile environment. His promotion caused certain Bonanno Crime Family members to feel nepotism had created an unfair advantage for him. The privately-educated Bonanno had grown up in Arizona, far away from the streets in New York City. He seemed unsuited for his new role. [4] An anti-Bonanno group formed behind Gaspare DiGregorio, one of the senior men passed over.

Stefano Magaddino, LCN boss in Buffalo and Joseph Bonanno’s cousin, seized on the resentment and encouraged the anti-Bonanno group to rebel. [5] Magaddino had grown to dislike Bonanno because of a territory dispute in Canada and other perceived slights going back many years. Helping the anti-Bonanno group was Magaddino’s way of striking back at him. The Commission was predisposed against Joseph Bonanno by this time and supported the insurrection.

In an attempt to settle the dispute, the Commission expelled Joseph and Bill Bonanno from their own crime family and ordered them to cease all LCN activities. They may have even put out murder contracts on the two men. Joseph and Bill Bonanno ignored the Commission edict and fought to keep control of their crime family. Family members were forced to line up behind one faction or the other and to take up arms.

On October 21, 1964, eight months after Bill Bonanno was made consigliere, and a month after the Bonannos were deposed by the Commission, Joseph Bonanno was kidnapped in New York City and wasn’t seen again for nineteen months. The kidnapping, which may have been a hoax staged by Joseph Bonanno himself, left Bill Bonanno alone on the street to represent his father’s interests. [6] It’s also when the “Banana War” informant began to “talk.”

The FBI was surprisingly well-informed through much of the “Banana War,” which lasted on-and-off between 1964 and 1968. Federal agents received a regular flow of Intel from listening devices planted in mob hangouts and from a Bonanno Crime Family member close to the situation.

The FBI knew, among other things, what soldiers remained loyal to Joseph Bonanno, who was gunning to replace him and the state of negotiations between the two sides. They even knew how the Commission tried to influence the outcome of the conflict.

All of the Intel ended up in FBI reports. A very small number of these reports that deal directly with the “Banana War” are now declassified and a couple of them contain clues that can be used to help identity the informant. (His identity was kept secret behind a redacted informant symbol code known only to the FBI.)

An FBI report from June, 1967, describes the FBI’s attempt to use an old case agent to revive a confidential relationship with a highly valued Bonanno Crime Family informant that had cooled off. [7] The report includes details about the informant that are so peculiar to him that his true identity is difficult to hide.

FBI discussions of the Bonanno Crime Family informant are shown in the following documents (click to view):

Magaddino

The description of the informant and his circumstance resembles Bill Bonanno in every way. Like the informant, Bonanno had to deal with a “personal problem involving his father” after Joseph Bonanno was kidnapped and he was left to lead the crime family against the anti-Bonanno forces. He was a sitting duck with a murder contract on his head.

Men that Bill Bonanno would have naturally turned to for help in the past, like Joseph Magliocco or Stefano Magaddino, were dead or had turned against him. This probably created an incredible amount of angst in him. FBI agent Richard Anderson likely exploited this vulnerability to gain his confidence and develop him as an informant. According to the report, Bonanno was an enthusiastic and valuable source, at least early on.

Bonanno’s problem was partially resolved when Joseph Bonanno reappeared and resumed control of the crime family. This is probably when the informant stopped cooperating at the high level he had in the past and became “difficult to handle.” It would seem only natural that Bill Bonanno would be less inclined to talk, given that it was his father’s absence that caused him to cooperate in the first place. The transfer of his original FBI handler, Richard Anderson, probably further dampened his enthusiasm to talk.

Larry Gallo

Lawrence "Larry" Gallo led a group of disgruntled Colombo Crime Family members (then known as the Profaci Crime Family) against boss Joseph Profaci. The Gallo faction, like the anti-Bonanno group, was encouraged to rebel by senior members in other crime families. [20] Following an attempt on his life, Gallo, like Bill Bonanno, appears to have buckled under pressure. He began to secretly share confidential information with the FBI. [21] The FBI discovered that “internal strife” provided a good opportunity to develop confidential informants. [22]

Like the informant, Bill Bonanno faced an uncertain future in the underworld. If things had gone his way, Bonanno likely would have succeeded his father as boss of the Bonanno Crime Family and probably would have ended up with a seat on the Commission, like the other New York bosses.

But it could have as easily gone the other way, as it eventually did. Bill Bonanno’s enemies wanted him gone and had tried to murder him on more than one occasion. Things were stacked against him. As the report says, he risked losing “his standing in the “family”” if the anti-Bonanno group prevailed. No other Bonanno Crime Family mobster in line to be boss fit this complete profile.

The two leaders of the anti-Bonanno group, Gaspare DiGregorio and Paul Sciacca, might have ended up in control of the crime family like the informant. But DiGregorio and Sciacca can be eliminated as potential suspects because neither man had a “personal problem involving his father” that needed the help of the FBI. Both mobsters were old men and their fathers were dead.

We don’t have a report indicating if the informant met up with his old case agent, but it does look like he made peace with the FBI. An FBI report produced in August, 1967, two months later, includes confidential information that only could have been supplied by Bill Bonanno. [8]

An informant gave federal agents a high-level update on the latest secret meeting between Bill Bonanno and the anti-Bonanno opposition. He identified Paul Sciacca, Pete Crociata and Frank Mari as the new leading members of the anti-Bonanno group. Gaspare DiGregorio had been forced to step down. Mari was Sciacca’s “physical support” while Crociata handled the “old timers.” He said a compromise between the two sides was unlikely because Sciacca wanted to be “boss.”

He told agents that Bill Bonanno always carried a gun because “he would rather be caught by the police with one, than to be caught by ‘others’ without one.” [9]

The informant was plugged in enough to be able to update federal agents on the activities of the other crime families. He said that the Lucchese Crime Family was being “tight lipped” about a possible successor to replace former boss Thomas Lucchese, who had died recently. They wanted to avoid the kind of “outside” interference that happened in the Bonanno Crime Family.

A few months after Bill Bonanno was persuaded to resume cooperating with the FBI, three members of the anti-Bonanno opposition were machine-gunned to death in the most violent episode in the entire “Banana War.”

The FBI’s stated objective when recontacting Bill Bonanno in 1967 was “to instil in him the proper perspective” and to “lay the groundwork for accelerated activity on his part in the interest of the Bureau.” They wanted Bonanno to “rise to the head of his ‘family’ and perhaps to eventually gain on a seat on the ‘Commission.’”

What part did the FBI’s ambition to have a source at the highest levels of LCN play in the violence? Bill and Joseph Bonanno had lost most of their rank-and-file support by this time. Did the FBI actively encourage Bill Bonanno to continue to fight beyond his intended limit?

He also told them how the Colombo Crime Family was trying to take advantage of the Bonanno civil war by increasing its area of influence in Brooklyn. Joseph Colombo had taken over the old Profaci Crime Family a few years earlier with the blessing of Carlo Gambino and Thomas Lucchese.

Colombo

According to the informant, Joseph Colombo wanted Paul Sciacca to become boss because he felt that he could “control” Sciacca. With Sciacca under his thumb, Colombo thought he could then take over parts of the Bonanno territory in Brooklyn and eventually end up as the most powerful crime boss in New York City.

The quality of the Intel indicated the source had to be a senior member of the Bonanno Crime Family. In fact, the report noted that the informant “explained that any information regarding LCN matters will be limited to the principals involved, and will not be a matter of common knowledge to all LCN members.”

But what really points to Bill Bonanno as the source in this report is the ability of a single individual to combine high-level information about the Bonanno Crime Family and other LCN families with details about Bonanno’s personal life that very few people would know.

For example, the same informant went on to tell federal agents about a recent trip Bill Bonanno made alone to Europe to visit his mistress. He was able to reveal the exact length of the trip, the itinerary, the full name of the mistress and what they did together. He gathered the information and shared it with the FBI within two weeks of Bonanno’s return from Europe. It seems unlikely that Bonanno would brag in detail to a criminal associate (who happened to be an informant) about these things in the middle of the “Banana War.” And this isn’t the kind of information someone would typically learn secondhand.

It’s hard to know when Bill Bonanno first began to talk, but we can speculate on a timeline based on a few clues.

We know he wasn’t talking anytime before September, 1964. An FBI report produced that month shows federal agents had wanted to arrange an interview with Bill and Joseph Bonanno “in an attempt to bring about their cooperation through the discreet use of information that their lives may well be in danger.” [10] And we know the FBI has also stated that Bonanno was persuaded to cooperate because of a “problem involving his father.” So that would suggest he wasn’t cooperating before Joseph Bonanno disappeared on October 21, 1964.

Author Gay Talese wrote a history of the “Banana War” with Bill Bonanno’s participation. According to Talese, Bonanno was consumed with his own image and wondered if he would “measure up” to his father. Bonanno is repeatedly quoted in the book asking himself if he would be “capable of withstanding the worst that might come along” or would he “panic” under pressure? Bonanno told Talese that he was confident that he could handle anything that came his way. By the time he confided these things to Talese, Bonanno had already shared confidential information with federal agents. [23]

Bill Bonanno

Furthermore, Bill Bonanno wrote in his memoirs that after his father was kidnapped, he fled New York City for about a two-week period for his own safety. He spent the whole time hiding out in close quarters with other Bonanno Crime Family members. According to Bonanno, they were never out of each other’s sight. That would seem to give him little opportunity to speak with the FBI anytime before the second half of November, when he returned to New York City. [11]

The first inkling that a Bonanno Crime Family informant might have become active is found in an FBI report dated December 23, 1964. [12] It appears to refer to an informant from New York City who had “recently” visited Canada to consult LCN members in the area. The report is redacted in spots but a clear reference is made to Bonanno Crime Family members in Montreal. The informant isn’t explicitly identified as a Bonanno Crime Family member but they were the only New York City crime family that had a significant presence in Quebec and would probably be the only crime family that would need to “consult” anyone in the area.

Although it’s hard to say for sure, the informant profile is consistent with Bill Bonanno and suggests he began to talk sometime between mid November and late December. Bonanno was a regular visitor to Montreal when his father resided briefly in the city. He would also meet with members of the local Bonanno group loyal to him. There is no evidence that more than one Bonanno Crime Family member-informant from New York City was operating in 1964 and certainly not one that was traveling to Montreal.

Bill Bonanno’s decision to cooperate with the FBI was fallout from his father’s battle to retain control of his crime family. It might seem improbable that the son of a legendary Mafioso could be the “Banana War” informant, but we know some surprising and unexpected people have secretly broken the code of silence.

The informant’s old case agent was Richard Anderson. He was assigned to monitor and investigate the Bonanno Crime Family in the 1960s, before he transferred to a different field office. Anderson was the agent that first convinced Bill Bonanno to talk. Bonanno specifically arranged to have Anderson arrest his father when he emerged from hiding in 1966. In his memoir, Bonanno refers to him as “Dick” Anderson, which suggests an intimacy between the two men. [24]

Former FBI agent Anthony Villano, who wrote about his experiences handling LCN informants in the 1960s, said the identity of some of them would “shock” people. [13] Villano very well might have been referring to someone like Bonanno. There’s no doubt that Bonanno did show a later tendency to reveal confidential details about his life in books and in interviews.

But why did Bill Bonanno cooperate in the first place? The FBI stated Bonanno became an informant, in part, because his father was kidnapped. However, it’s hard to see then how the FBI could “capitalize” on the kidnapping if Bonanno was in on the hoax and he knew his father was safe all along. That would tend to suggest Bonanno was in the dark about the kidnapping, at least initially (even if it was staged by his father). [14]

It also raises the question: why would Bill Bonanno continue to cooperate after his father emerged from hiding in 1966 and returned to his side. (It appears he did stop cooperating for a short period.) What was the upside for him? Did he receive some unknown benefit? Or was cooperating part of some strategy to further the war effort against the anti-Bonanno group?

Evidence suggests Bill Bonanno may have continued to talk right up to the time he and his father worked out a deal to retire to Arizona in 1968 and give up all claims on the Bonanno Crime Family. [15] It’s unclear if he continued to cooperate beyond that.

What’s clear though is that Bill Bonanno made an unlikely mob boss. His duty to his father compelled him to play a part that wasn’t made for him. Bonanno summed up things better than anyone when he said “I did what I had to do, not what I wanted to do.” [16] And that worked to the advantage of the FBI.

“Now I guess you will make another Valachi out of me.”

- Bill Bonanno

Some time after this article was completed, I received excerpts from an early interview Bill Bonanno gave to the FBI. These documents clearly establish that Bonanno shared confidential information with law enforcement. [17]

The interview took place in the county jail in Tucson, Arizona, in the early morning of January 1, 1965. Bonanno had arrived in Tucson, his hometown, a few days earlier after hiding out in New York and New England for the two months. He was promptly arrested as a material witness into his father’s kidnapping. He spent two days in a prison cell, where he secretly agreed to be interviewed by the FBI.

The interview took place over five hours, so much of what Bill Bonanno likely revealed is not included in the excerpts. The report was produced by the FBI’s New York Office which suggests agents from there traveled to Tucson to conduct the interview. Richard Anderson from the New York Office was acknowledged to be the FBI agent that turned the “Banana War” informant.

If we assume Anderson traveled to Tucson to conduct the interview (it’s not clear from the report that he did so), it raises the suspicion that Bonanno may have already explored the possibility of talking with him before this. [18] Otherwise, why talk with Anderson when Bonanno could have easily talked to the local agent who arrested him and whom he knew quite well. [19] Did Bonanno ask for Anderson? Was he sent because Bonanno fell under the purview of the New York Office? Did Bonanno crack after only one night in jail? Or had the groundwork for this interview been laid by Anderson sometime earlier?

Bill Bonanno’s statements about his father’s kidnapping were generally consistent with what he later wrote in his memoirs.

Bill Bonanno told agents he had no prior knowledge of his father’s kidnapping and put the blame on the “rebel group.” He added that that he didn’t “know the fate of his father.” He said his father’s soft heart was his undoing. Instead of crushing the rebel group at the first sign of trouble, Joseph Bonanno insisted to his son that “we must try to settle our differences without bloodshed.”

Bonanno seemed resigned to his loss of stature. He told agents, “Why do you bother with us, we’re nobody now.” And then elsewhere, he says, “Now I guess you will make another Valachi out of me.”

1 Bonanno, Joseph, with Sergio Lalli, A Man of Honor: The Autobiography of Joseph Bonanno, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1983, p. 365-366.

2 FBI, La Cosa Nostra; Conspiracy, San Diego Office, Nov. 29, 1968, NARA Record Number 124-10288-10450; FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Memorandum C.A. Evans to Mr. Belmont, Oct. 26, 1964, NARA Record Number 124-10217-10124; FBI, John Roselli, Los Angeles Office, Dec. 19, 1964, NARA Record Number 124-10215-10221.

3 FBI, Joseph Bonanno: Victim, Buffalo Office, Nov. 6, 1964, NARA Record Number 124-10353-10040; FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, Sept. 24, 1964, NARA Record Number 124-10278-10325. Bonanno argued the election of his son to consigliere was an internal Family matter that didn’t concern the Commission. Despite some negotiations, Bonanno likely had no intention to meet with the Commission since he knew he would be outmaneuvered and outvoted by the anti-Bonanno bloc.

4 FBI, Vincent A. Scro, New York Office, Oct. 30, 1963, NARA Record Number 124-10339-10155. Stefano Magaddino called him “stupid,” a ”cucumber” and a “jerk.”

5 Magaddino was also DiGregorio’s brother-in-law.

6 FBI, Summary from Sicilian, Buffalo Office, Oct. 29, 1964, NARA Record Number 124-10353-10019. Bonanno claimed he was kidnapped on the orders of Stefano Magaddino. A listening device that surveilled Magaddino revealed nothing unusual on the day Bonanno was kidnapped. In reality, many suspect Bonanno faked his own kidnapping to avoid testifying in front of a grand jury and to buy himself time in his fight against the Commission.

7 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, June 2, 1967, NARA Record Number 124-10290-10027.

8 FBI, NY-REDACTED-C-TE TECIP New York Division, New York Office, Aug. 11, 1967, NARA Record Number 124-10287-10379. FBI agent Richard Wernersbach handled this informant suggesting Anderson was able to persuade Bonanno to work with someone else; Bonanno, Bill with Gary B. Abromovitz, The Last Testament of Bill Bonanno: The Final Secrets of a Life in the Mafia, New York: Harper, 2011, p. 303. Wernersbach was familiar to Bonanno.

9 Bill Bonanno, Bound By Honor: A Mafioso’s Story, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999, p. 199. Bonanno tells a somewhat similar story in his memoir: “The soldier thought about it for a minute and then said, 'Nahh, I think it’ll be better if you catch me with [the gun] than if I let them catch me without it.'”

10 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Director to Legat, Ottawa, Jan. 14, 1965, NARA Record Number 124-10223-10344; FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Memorandum C.A. Evans to Mr. Belmont, Sept. 4, 1964, NARA Record Number 124-10223-10454.

11 Gay Talese, Honor Thy Father, New York: World Publishing, 1971, p. 31-53; Bound By Honor, p. 155-156. We have to take Bonanno’s word for this alleged trip. The only companion identified by name was Frank LaBruzzo and he was dead by the time Bonanno related the story. The trip would offer the perfect cover story if Bonanno was actually speaking with the FBI.

12 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Director to Legat, Ottawa, Jan. 14, 1965, NARA Record Number 124-10223-10344. (The report from Dec. 23, 1964, isn’t available but is referenced in this report.) Bonanno may not have been cooperating at the time he “recently” visited Montreal. The cooperation could have begun later.

13 Villano, Anthony with Gerald Astor, Brick Agent: Inside the Mafia for the FBI, New York: Quadrangle, 1977, p. 85.

14 Was Joseph Bonanno protecting his son and giving him deniability? Or does it tell us something about what he thought of him?

15 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, Aug. 2, 1968, NARA Record Number 124-10226-10190; FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, Oct. 31, 1967, NARA Record Number 124-10293-10325. These sources are consistent with Bonanno’s profile.

16 Niagara Falls Gazette, Saturday, Oct. 9, 1973.

17 Bonanno’s name was used throughout the report which suggests he hadn’t yet been designated an official source and given an informant symbol code. If that’s true, the informant referenced in Note 12 may be someone else. (Thank you to the individual, who wishes to remain anonymous, for supplying this document.)

18 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Director to Legat, Ottawa, Jan. 14, 1965, NARA Record Number 124-10223-10344. This report suggests Bonanno may have already explored the possibility of cooperating as early as Dec. 23, 1964.

19 Bound By Honor, p. 166. "Then the front door opened and several agents walked in, headed by an FBI agent I knew named Kermit Johnson, who had been on my case for some time, I said very pleasantly, 'Hiya, Kermit, howya doin’?'”

20 FBI, Criminal Intelligence Digest, Memorandum C.A. Evans to Mr. Belmont, May 20, 1964, NARA Record Number 124-10287-10190.

21 FBI, La Cosa Nostra Detroit Division, New York Office, March 14, 1963, NARA Record Number 124-10205-10450. Lawrence Gallo is source T-27 in this report. Gallo may have been the first LCN member to share details about the Commission. Before this, law enforcement only knew about the Commission through Intel picked up through listening devices.

22 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Director to New York Office, Nov. 21, 1967, NARA Record Number 124-10289-10195.

23 Honor Thy Father, p. 55

24 Honor Thy Father, p. 201-206.

25 The Last Testament of Bill Bonanno, p. 299-300.