A number of crime history writers have asserted that the Sicilian Mafia - or Sicilian Black Hand Society - was actively engaged in extortion and murder in the city of New Orleans as early as 1855. While that is possible, evidence is sorely lacking.

Proponents have supported this claim by pointing specifically to what they insist was a brutal, stabbing death of extortion target Francisco Domingo in that year. They also refer far more vaguely to what they say are similar cases. It is a significant matter, as this could turn the clock back considerably on the earliest documented Sicilian underworld activity in the United States. Unfortunately, the story of Domingo as presented by these writers is provably false.

Like a number of oft-repeated Mafia history falsehoods, this one can be traced to the fertile mind of author David Leon Chandler.

Chandler was born in Covington, Kentucky, in 1937. [1] According to a New York Times obituary, Chandler managed to cut short his college education by gambling his Boston College tuition funds on a losing horse. He served in the merchant marine and then became a journalist, winning the Pulitzer Prize for public service in 1962 for helping expose corruption in the Bay County, Florida, sheriff's office. He wrote for a New Orleans newspaper between 1962 and 1964, moved on to Life magazine, and became a freelancer in the 1970s. In 1975, he wrote Brothers in Blood, his version of U.S. organized crime history. Chandler wrote several other books before he died in January 1994 at the age of fifty six. [2]

In his 1975 book Brothers in Blood, Chandler stated that the "earliest report of an Italian criminal society in America" was in 1855. He explained that notes demanding money and promising death for non-payment were received by "several citizens of New Orleans." These early letters were signed "the Black Hand" or something similar, and they "often bore the inky imprint of a hand." Later letters were signed "the Mafia," according to Chandler. [3]

Chandler then supported his assertions by supplying the details of a particular Black Hand event. The story, which contained only trace amounts of truth, was confined in a single paragraph of the book:

On January 4, 1855, the New Orleans newspaper The True Delta reported that the body of a truck farmer named Francisco Domingo had been found on the Mississippi levee. He had been stabbed eighteen times and his throat slit savagely. Despite his Spanish name, Domingo was identified as Sicilian, one of the three thousand Italians who had arrived in New Orleans since 1841. His widow gave police a note Domingo had received. He would die, the note said, unless he paid five hundred dollars. At the bottom appeared a large, inky, black hand. Mrs. Domingo said that in the past six months her husband had received several of these Black Hand notes. All had been delivered by strangers, some slipped into his palm, others into his pocket, and some left on his wagon. He had told her they were written by teen-agers who were stupid but not dangerous. The case was never solved. [4]

These appear to be the key details in Chandler's tale:

Chandler revealed no source for the many details of the Domingo extortion and murder except for his mention of January 4, 1855, issue of the True Delta. That is a problem, and we'll deal with it shortly.

As he assembled the 1977 book, The Black Hand: A Chapter in Ethnic Crime, author Thomas Monroe Pitkin was aware of Chandler's statements about the supposed early Black Hand in New Orleans. Pitkin (born October 6, 1901, in Akron, Ohio, and died January 22, 1988, in the same city [5]) was a professional historian, who worked for decades with the Park Service and spent fifteen years as historian at the Statue of Liberty. To Pitkin's credit, he did no more than note the existence of Chandler's tale: "David Chandler, in his recent rather startling study of criminal brotherhoods, has shown that the symbol of a black hand was actually used for extortion purposes in Louisiana as early as 1855." [6] Pitkin made no effort to correct Chandler's story of Francisco Domingo, but at least did not repeat it.

Half a dozen years later, the tale fell into the hands of Dr. Michael L. Kurtz, a Louisiana history professor with a fondness for sensational history. Kurtz took the ball and ran with it. Born August 26, 1941, in New Orleans, Kurtz earned degrees from the University of New Orleans, University of Tennessee and Tulane University. He became a history professor at Southeastern Louisiana University, where he was widely known for teaching, writing about and otherwise promoting conspiracy theories regarding the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. [7]

He wrote about the 1855 Domingo incident for a 1983 article, entitled, "Organized Crime in Louisiana History: Myth and Reality." The title promised a more frank historical assessment than the article actually provided. Here's what Kurtz wrote about Domingo:

On January 3, 1855, the body of Fransisco [sic] Domingo, a Sicilian truck farmer, was discovered on an embankment near the Mississippi River in New Orleans. He had been stabbed over a dozen times, and his throat was slit from ear to ear. Domingo's widow gave investigating officers a note her husband had received a few days before the murder. The note demanded that Domingo pay its anonymous author $500 in return for his life. Near the bottom of the note, stamped in black ink, lay the imprint of a black hand. In the ensuing five years, six similar murders occurred in New Orleans, each involving a victim of Sicilian or Italian origin who had received a threatening note containing the black hand symbol. [8]

He provided two footnotes for this paragraph. The first, placed after the mention of the hand-shaped ink stamp, referred to the New Orleans True Delta issue of January 4, 1855 - the same issue cited by Chandler. The second footnote, placed after the mention of the six additional killings, cited Page 67 of Chandler's book, Brothers in Blood (my first edition of Brothers in Blood has its related discussion on Page 70). [9] So, Kurtz, too, basically claimed that his story was based on the True Delta issue of January 4, 1855. We'll get to that.

The details of Kurtz's account are these:

Despite the mention of True Delta in the footnote, Kurtz's account was merely a rewrite of Chandler's with some minor differences. Both provided similar identification for Domingo and saw him as a victim of a Black Hand attack. Kurtz reduced the stab wound total by about a third, from eighteen to more than twelve, but added the "ear to ear" description of the cut to Domingo's throat. Kurtz (perhaps recognizing that to be reported in the True Delta of January 4, the event needed to happen on or before January 3) had Domingo found one day earlier than Chandler, and put the body on an embankment rather than along the levee. The ink handprint described by Chandler may have become an ink stamp in Kurtz's account.

When author Stephan Talty tackled the subject for his 2017 book, The Black Hand: The Epic War Between a Brilliant Detective and the Deadliest Secret Society in American History, he used Kurtz's article as his sole source. Talty, born in 1965 in Buffalo, New York, worked as a journalist before becoming a freelance writer. [10] He injected some atmosphere and color into the Domingo story. No source was provided for these additional details. They likely came from Talty's imagination.

Talty dealt with Domingo matter in the very first paragraph of his book's first chapter. Here is his account:

On January 3, 1855, a dead man lay on an embankment of the Mississippi River not far from New Orleans as the water just a few feet from his out-flung hand rolled southward toward the Gulf of Mexico. Even from a distance, it would have become clear to any observer that the man's passing had been a violent one. His shirt was covered in blood and pierced at several points; he'd been stabbed over a dozen times. In addition, his throat was cut from ear to ear, and the blood from the wound was caking thickly in the heat. The man's name was Fransisco [sic] Domingo, and he was the first known victim of the Black Hand in America. [11]

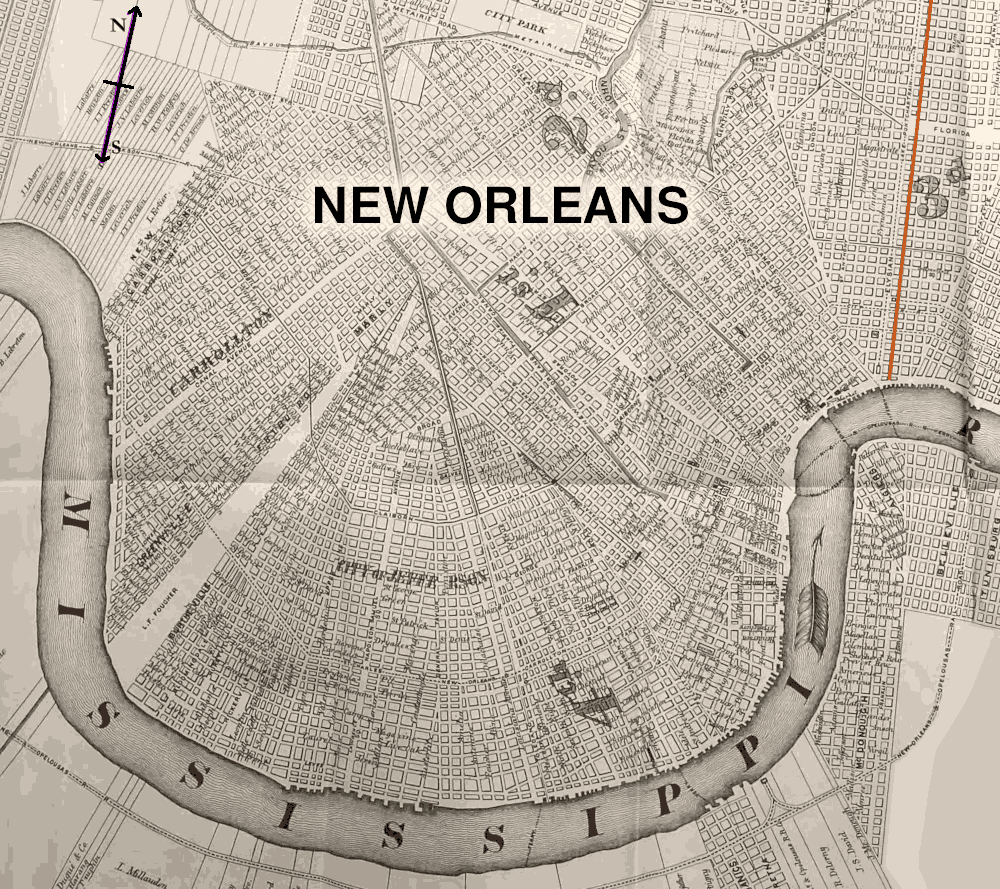

The author, perhaps unwittingly, suggested a fairly specific location for the discovery of Domingo's body by indicating that it was found beside the south-flowing Mississippi River. The Mississippi snakes its way generally eastward in the region and curves around the city of New Orleans, carving the "crescent" of the Crescent City. In the New Orleans area, the river flows south only at the eastern, "Uptown" / upriver edge of the city. If the "rolled southward" comment was anything more than invented, it would point to the Uptown edge of New Orleans as the spot where Domingo's body was found.

Talty repeated Kurtz's "ear to ear" description of the cut to Domingo's throat, reused the total of a dozen knife wounds and even copied from Kurtz the misspelling of Domingo's first name.

The author apparently on his own created the idea of the blood "caking thickly in the heat," an idea that never would have occurred to New Orleans native Kurtz. The southern metropolis of New Orleans generally does not experience much in the way of "heat" in January. That is statistically the city's coldest month, when daytime high temperatures climb just over 60 degrees Fahrenheit, much lower than normal body temperature. [12]

Other writers, perhaps influenced by Kurtz's credentials, have followed in Talty's footsteps and repeated the Domingo tale (though we haven't yet seen anything to rival Talty's embellishment). In 2019, writer Thom L. Jones inserted the supposed Black Hand story into a biographical article about New Orleans crime boss Carlos Marcello. [13]

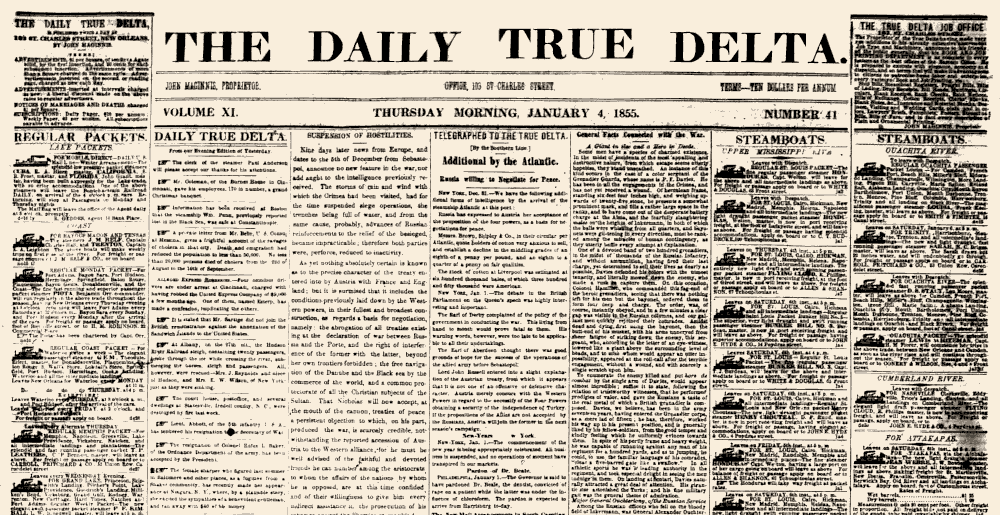

The January 4, 1855, issue of the True Delta was explicitly cited by both Chandler and Kurtz, and it can be considered an indirect source for Talty, who relied on the Kurtz account. The True Delta newspaper was first launched in the 1840s. In 1855, it was published by John Macinnis in daily and weekly editions out of an office on St. Charles Street in New Orleans. In that period, the daily edition was released in the morning (an Evening True Delta began publication in 1858), requiring an articles deadline the previous afternoon or evening. [14]

Copies of the January 4, 1855, True Delta are difficult to locate, and this may have prevented others from disputing the Chandler and Kurtz tales. Some years ago, Becky Smith, head of Reader Services of the Historic New Orleans Collection at the Williams Research Center, was kind enough to send over copies of the four-page newspaper. [15]

January 4, 1855, issue of the True Delta. (Historic New Orleans Collection)

Mostly, the issue consisted of local brief announcements, short telegraphic news items from around the country and around the world, shipping news and classified advertisements. Nowhere in the issue was there mention of the stabbing murder of Francisco Domingo - no discussion of bodies found on river embankments or Sicilian extortion or ink handprints or multiple stab wounds or any of the components of the Black Hand story. (Rebecca Smith advised that she examined the January 5, 1855, issue of the paper and found no reference to Domingo in that one either.) [16]

The citation of that issue by both Chandler and Kurtz was an error. At least. It is difficult to accept that two writers of history made precisely the same mistake in a source citation. Kurtz's additional reference of Brothers in Blood proves that he was aware of Chandler's tale when he wrote his own and suggests that he simply copied the story along with the incorrect source citation from Chandler's book.

Readers of history should keep in mind (now and always) that some writers of history insert false details throughout their works in order to track plagiarism and increase copyright protection. Factual data, regardless of an author's expenses and efforts to acquire and present it, receives little in the way of copyright protection, while fictional elements - even deliberate lies - are entirely protected under the law. [17] The possibility exists that Chandler created an incorrect source to trap those who might mindlessly copy his material and/or to protect the work from unauthorized reproduction. We may wonder if he dreamed up the entire Domingo tale - later repeated by Kurtz and Talty and others - with those same motivations.

The utter absence from the January 4 True Delta of any report of the demise of a Francisco Domingo actually begins to make a great deal of sense, once the truth of the story is learned.

There is actually a fair amount of material on Francisco Domingo in the historical record. It strongly disagrees with the Black Hand murder story presented by Chandler and others.

The sources indicate that a man named Francisco Domingo was stabbed and mortally wounded at about five thirty in the afternoon of Thursday, January 4, 1855. [18] The incident occurred after presstime for the January 4 issue (and the January 5 issue, as well) of the True Delta. This explains why the cited newspaper was not and could not have been the source used by Chandler and Kurtz.

The stabbing reportedly occurred during a quarrel between Domingo and a man named Guillermo Ballerio. Domingo was a fisherman, not a farmer as claimed by Chandler and Kurtz. Ballerio was a fisherman, as well. According to the published accounts, the men resided in the same home on Marigny Street, along with a number of other fishermen. (The location was Downtown / downriver of the center of New Orleans, where the nearby Mississippi flows toward the northeast and east.) During supper inside the shared home, an argument erupted, and Domingo and Ballerio went outside to settle it. Domingo quickly gained an upper hand in the fistfight, and Ballerio responded by pulling a knife and plunging it once into Domingo's side. [19]

Map of New Orleans. Orange line shows location of Marigny Street.

Just once. Not eighteen times or even twelve times. Domingo suffered only this single knife wound to the body. No wound at all was inflicted on his throat.

Friends rushed Domingo to the Charity Hospital in New Orleans. The wound penetrated deep into Domingo's left side. Doctors were unable to do much more than make him comfortable and await the inevitable. Domingo lingered for a time. A newspaper of January 6 stated that he "was lingering on with but faint hopes of his recovery." [20]

The case that Chandler claimed was "never solved" was actually very quickly solved. Ballerio was immediately arrested. With Domingo still alive, Ballerio was initially charged with stabbing him. He was arraigned on that charge before Recorder Seuzenau on January 5. [21] When Domingo passed away in the hospital - not on the levee or on a river embankment - the charge was changed to murder. [22]

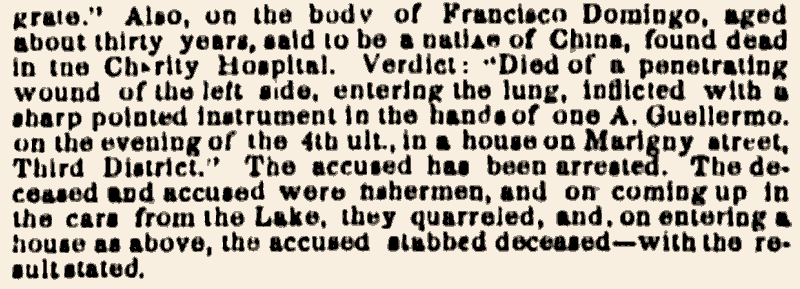

A coroner's inquest was held near the end of January and found that Domingo, said to be about thirty years old, "died of a penetrating wound on the left side, entering the lung, inflicted with a sharp pointed instrument in the hands of one A. Guellermo [sic] on the evening of the 4th ult., in a house on Marigny street, Third District." [23]

Report on inquest printed in February 2, 1855, issue of New Orleans Commercial Bulletin.

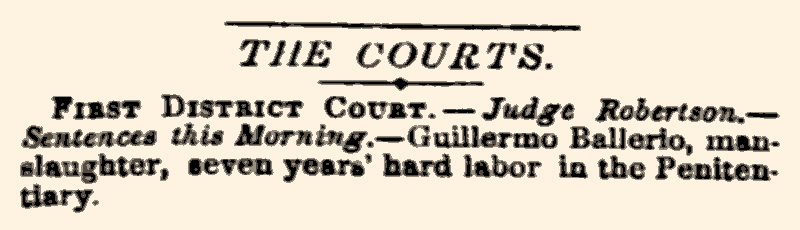

A preliminary examination of Ballerio on the murder charge occurred before Recorder Seuzenau early in February, and Ballerio was held for trial. The trial occurred in Judge Robertson's First District Court in June. [24]

In its reports of the proceedings, the New Orleans Daily Picayune newspaper stated that both Domingo and Ballerio were fisherman and "Manilla men." An earlier report in the Picayune described the two men as "Spaniards." A report in the New Orleans Bee said they were "natives of the island of Manilla in the East Indies." The New Orleans Commercial Bulletin reported that Domingo was "a native of China." [25]

These descriptions provide an explanation for something that appeared to concern Chandler: the author mentioned that his supposed Sicilian victim of the Black Hand had a Spanish-sounding name. The term "Manilla men" (elsewhere seen as "Manilamen") was applied to natives of Manila, busy commercial center of the Philippines, which had been a colony of Spain since the 16th century. Filipinos were used as crewmen aboard Spanish vessels as they traveled around the world, and Filipinos were among the earliest Asian immigrants to settle in the New Orleans area, possibly arriving as early as the 1760s. In business, many New Orleans-area Filipino Americans specialized in fishing and shrimping. [26]

Possibly supporting the idea that Domingo was a Spanish/Filipino immigrant are the New Orleans port's arriving passenger lists from the period. The Spanish Brig Salvadora reached New Orleans, after a stop in Havana, Cuba (another Spanish colony at that time), on September 13, 1847. Aboard the ship was "Snr. Francisco Domingo," twenty five, a Spanish citizen. Another list, dated 1849 (as a handwritten "7" can be confused with a handwritten "9," these two lists may refer to the same event), shows a twenty-five-year-old Francis Domingo as an immigrant to New Orleans, arriving on a ship from Havana. [27]

At the conclusion of the trial, a jury found Guillermo Ballerio guilty of manslaughter, the unpremedited and unintended killing of Francisco Domingo. On the morning of June 24, Judge Robertson sentenced Ballerio to serve seven years of hard labor in the state penitentiary. [28]

News of sentencing from June 24, 1855, issue of New Orleans Daily Picayune.

Nowhere in available accounts of the case was there any mention of a wife of Domingo, any farming activity, any Sicilians, any Black Hand, any extortion letters. These details and every other significant detail from the stories presented by Chandler, Kurtz, Talty, et al. were entirely false. While some evidence may exist for 1850s-era Black Hand activity in the immigrant Sicilian population, the tragic tale of Francisco Domingo certainly is not it.

We can only guess at Chandler's motivation for concocting the brutal Black Hand slaying story and his reaction to its acceptance as crime history. He lived long enough to recognize that his one-paragraph lie had somehow taken root and was propagating through the works of others.

1. David L. Chandler, Colorado Death Records, Jan. 23, 1994.

2. "David Chandler, 56, newspaper reporter who won Pulitzer," New York Times, Jan. 26, 1994, Section B, p. 6; "Public Service," The Pulitzer Prizes, pulitzer.org (the prize was awarded to the Panama City FL News-Herald); David L. Chandler, Colorado Death Records, Jan. 23, 1994.

3. Chandler, David, Brothers in Blood: The Rise of the Criminal Brotherhoods, New York: E.F. Dutton & Co., 1975, p. 67.

4. Chandler, David, Brothers in Blood: The Rise of the Criminal Brotherhoods, New York: E.F. Dutton & Co., 1975, pp. 69-70.

5. Indexed Record of Births - Summit County, Ohio, Vol. 4, p. 232; Thomas Monroe Pitkin World War II Draft Registration Card, serial no. T1373 order no. T10321, local board no. 13, Akron, Ohio, Feb. 16, 1942; Thomas M. Pitkin, Ohio Death Records, Summit County, registrar's certificate no. 5968, Jan. 22, 1988; "Thomas Pitkin, historian for Statue of Liberty," Akron OH Beacon Journal, Jan. 24, 1988, p. F8.

6. Pitkin, Thomas Monroe, and Francesco Cordasco, The Black Hand: A Chapter in Ethnic Crime, Totowa, New Jersey: Littlefield, Adams & Co., 1977, p. 46.

7. "Michael L. Kurtz," Spartacus Educational, spartacus-educational.com; "A history professor who studied the Kennedy assassination for...," UPI archives, upi.com, March 27, 1982.

8. Kurtz, Michael L. "Organized Crime in Louisiana History: Myth and Reality," Louisiana History, Fall 1983, New Orleans: Louisiana Historical Association, 1983, p. 355.

9. Kurtz, Michael L. "Organized Crime in Louisiana History: Myth and Reality," Louisiana History, Fall 1983, New Orleans: Louisiana Historical Association, 1983, p. 355.

10. Stephan Talty, Biography & Genealogy Master Index, Ancestry.com; "About," Stephan Talty, stephantalty.com, 2023.

11. Talty, Stephan, The Black Hand: The Epic War Between a Brilliant Detective and the Deadliest Secret Society in American History, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017, Chapter 1.

12. "NWS New Orleans / Baton Rouge New 30 Year Climate Normals," National Weather Service, weather.gov. The idea of blood coagulating quickly in hot weather may be supported by "Effects of temperature on bleeding time and clotting time in normal male and female volunteers," National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Researchers found that at 98 degrees Fahrenheit blood clotted three times quicker than at 71 degrees.

13. Jones, Thom L., "Out of Africa: The story of New Orleans Mafia boss Carlos Marcello," Mob Corner, Gangsters Inc., gangstersinc.org, April 7, 2019.

14. "The Daily True Delta (New Orleans, La.) 1849-1866," Directory of U.S. Newspapers in American Libraries, Library of Congress, loc.gov; "New Orleans Weekly True Delta (New Orleans, La.) 1851-186?," Directory of U.S. Newspapers in American Libraries, Library of Congress, loc.gov. The Library of Congress database states that the first issue of the Daily True Delta (Volume I, Number 1) was released on Nov. 18, 1849. Ordinarily, volume refers to a year's worth of issues, but volume numbers are sometimes advanced with changes in ownership or after publication interruptions. In January 1855, just six years after the True Delta began publication, it already labeled itself "Volume XI." Another oddity of the newspaper was its placement of the word "True" with a higher baseline than the other words in the Page 1 banner.

15. "RE: 1855 newspaper," email communications from Rebecca Smith, April 25, 2017.

16. New Orleans Daily True Delta, Jan. 4, 1855, pp. 1-4; "RE: 1855 newspaper," email communications from Rebecca Smith, April 25, 2017.

17. Writing & Copyright, publication of the United States Copyright Office, copyright.gov, January 2022.

18. "Third District: Another Probable Murder," New Orleans Daily Picayune, Jan. 5, 1855, p. 1; "Third District: Probable Murder," New Orleans Bee, Jan. 6, 1855, p. 1.

19. "Third District: Another Probable Murder," New Orleans Daily Picayune, Jan. 5, 1855, p. 1; "Third District: Probable Murder," New Orleans Bee, Jan. 6, 1855, p. 1; Third District: The Supposed Murder," New Orleans Daily Picayune, Jan. 6, 1855, p. 2; "The Courts," New Orleans Daily Picayune, June 20, 1855, p. 2.

20. "Third District: Another Probable Murder," New Orleans Daily Picayune, Jan. 5, 1855, p. 1; "Third District: Probable Murder," New Orleans Bee, Jan. 6, 1855, p. 1; Third District: The Supposed Murder," New Orleans Daily Picayune, Jan. 6, 1855, p. 2.

21. Third District: The Supposed Murder," New Orleans Daily Picayune, Jan. 6, 1855, p. 2.

22. The date of Domingo's passing is uncertain. It is known to have occurred within the month of January 1855.

23. "Inquests," New Orleans Commercial Bulletin, Feb. 2, 1855.

24. "Committed for murder," New Orleans Daily Delta, Feb. 11, 1855, p. 8; "The Courts," New Orleans Daily Picayune, June 20, 1855, p. 2.

25. "The Courts," New Orleans Daily Picayune, June 20, 1855, p. 2; "Third District: Another Probable Murder," New Orleans Daily Picayune, Jan. 5, 1855, p. 1; "Third District: Probable Murder," New Orleans Bee, Jan. 6, 1855, p. 1; "Inquests," New Orleans Commercial Bulletin, Feb. 2, 1855.

26. Perkins, Emily, "Coming to New Orleans: progressivism and Chinese exclusion," The Historical New Orleans Collection, hnoc.org, Aug. 4, 2023; Aguilar, Filomeno V., "Manilamen and seafaring: engaging the maritime world beyond the Spanish realm," Journal of Global History, Oct. 19, 2012.

27. Manifest of Brig Salvadora, list of passengers arrived from foreign ports in the port of New Orleans, quarterly abstract, September 1847; "Francis Domingo," U.S. Passenger and Immigration Lists Index, New Orleans, 1849, Ancestry.com. The man or men mentioned would have been about the same age as the Francisco Domingo who was fatally stabbed early in 1855.

28. "City intelligence," New Orleans Bee, June 21, 1855, p. 1; "The Courts," New Orleans Daily Picayune, June 24, 1855, p. 4.