A version of this article first appeared as a column in the August 2019 issue of Informer: The History of American Crime and Law Enforcement.

One persistent underworld legend relates to a supposedly widespread, Salvatore Lucania-orchestrated purge of men loyal to assassinated Mafia boss of bosses Salvatore Maranzano. The slaughter has been referred to as "the Sicilian Vespers."

Illustration of 1282 Sicilian Vespers uprising.

The term "Sicilian Vespers" originally (and, it turns out, inaccurately) referred to a Palermo uprising against an oppressive Angevin occupying force at about the time of the Easter holiday way back in 1282. According to tradition, the Sicilian community gathering for Vespers religious service on the eve of Easter (the violence actually began days after Easter), suddenly and brutally attacked the occupiers. Thousands reportedly were slaughtered in the uprising. [1] That event was later documented in the religion-centered history Lu Rebellamenti di Sichilia, written in the late thirteenth century, and became the subject of the romantic 1850s Giuseppe Verdi opera, entitled The Sicilian Vespers. [2]

The American Mafia-related version of the Sicilian Vespers legend occurred in late summer of 1931, about half a year after the end of the so-called Castellammarese War.

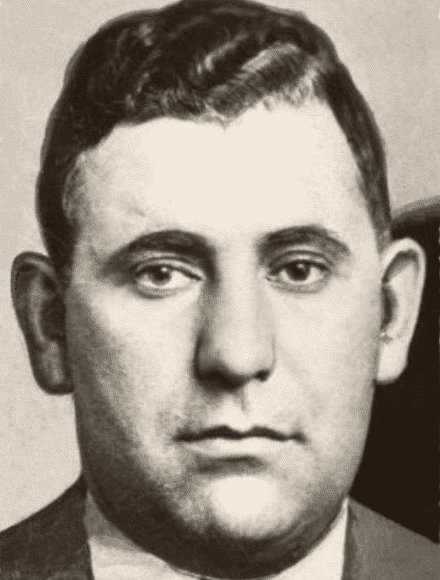

Masseria

In that war, mafiosi across the U.S. divided into violently competing camps led by Giuseppe "Joe the Boss" Masseria and Salvatore Maranzano. Masseria was boss of a rich and powerful Manhattan-based crime family and reigned as supreme arbiter - boss of bosses - over all the crime families in the American Mafia. Maranzano led an anti-Masseria force comprised of immigrant mafiosi from Castellammare del Golfo, Sicily, and their allies. Maranzano's side has been characterized as more conservative and traditional in its view of the Mafia than the liberal-minded Masseria, though this distinction may be based more on underworld propaganda than fact.

In April 1931, Masseria was assassinated by his own lieutenants, and the war concluded with Maranzano assuming the boss of bosses role. The following summer, Maranzano began secretly plotting the murders of underworld leaders he considered uncooperative. Chief among these was Salvatore "Charlie Luciano" Lucania, who had risen to lead the former Masseria organization. Lucania learned of the plans, and he and his allies moved against Maranzano, assassinating the boss of bosses at his Manhattan offices. The slaying of Maranzano occurred on September 10, 1931, reportedly the same date chosen by Maranzano for his move against Lucania and others.

According to the U.S. Sicilian Vespers legend, the Maranzano assassination was immediately followed by a carefully coordinated purge, a near-simultaneous mass murder of Maranzano loyalists across the country. The story was born within a decade of the supposed purge, and it quickly spread and grew.

While it is true that some mafiosi known to be friendly to Maranzano were murdered within a few days of the supreme boss's assassination, and some other killings were attempted without success, there is not evidence of a vast conspiracy or large numbers of coordinated attacks. Let's take a look at the evolution of the legend and the problems with the various versions of it.

The Maranzano assassination was not quite eight years in the past when Richard "Dixie" Davis, former attorney for gangster Arthur "Dutch Schultz" Flegenheimer, wrote about the purge of Maranzano men in an August 1939 article for Collier's magazine.

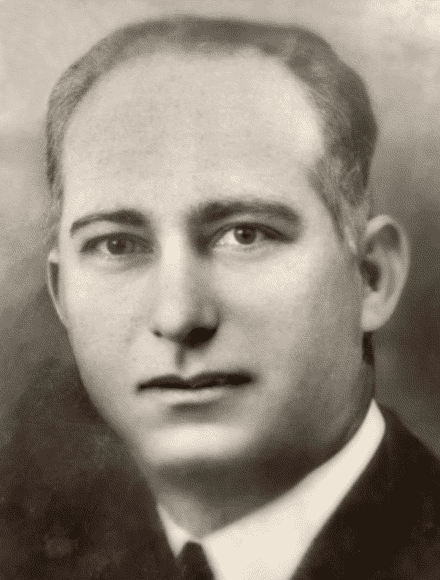

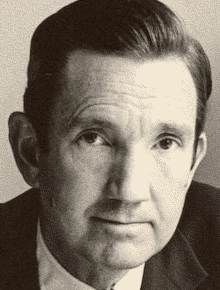

Davis

In his article, Davis said he was told of the purge by Dutch Schultz associate Abraham "Bo" Weinberg. During the Castellammarese War, Schultz was allied with "Joe the Boss" Masseria lieutenants Ciro "the Artichoke King" Terranova and Lucania. (Davis reported that East Harlem Mafia leader Terranova held a twenty-five percent share in Schultz beer and lottery rackets.) According to Davis, Schultz used Weinberg to keep in touch with "downtown" mobsters like Lucania and "Trigger Mike" Coppola, as well as to relay messages to Tammany Hall political bosses.

Weinberg told Davis that he personally participated in the murder of Maranzano (who he called "Maramanenza"). And Weinberg added, "At the very same hour when Maramanenza was knocked off, there was about ninety guineas knocked off all over the country. That was the time we Americanized the mobs."

Through the decades that followed the Davis revelation, many have referred to the "ninety" killed in the wake of the Maranzano assassination without noting the doubts clearly expressed by Dixie Davis in the same article:

I have never been able to check up on the accuracy of Bo's assertion that mass homicide took place in that single hour. But it is certainly true that all through 1931 there was a terrific number of Sicilian murders all through the country. They were casualties in the battle between the "greasers" or "greaseballs," who were unassimilated Sicilians, and the old-line mobsters, notably in Brooklyn and the Lower East Side of New York, for control of the Unione Siciliana [described as a modern version of the Sicilian Mafia]. [3]

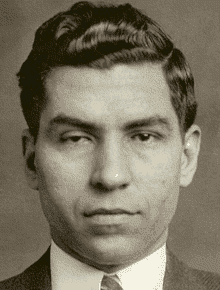

Weinberg

These comments by Davis call into question both the total number of killings and the Weinberg timeframe of an hour. It becomes clear that Davis's reference to "all through 1931" includes the months before Maranzano's assassination as well as those after. The murderous "Americanization" of the Mafia described by Davis could be viewed as including the Castellammarese War itself.

Davis may have been signalling that the purge figure included all the fatalities associated with that conflict and its aftermath. This view is supported by the fact that Davis proceeded in the same article to describe the events of the Castellammarese War.

(An additional reason to view the Weinberg comment as a misunderstanding was provided decades later, when the FBI estimated a Castellammarese War death toll of "approximately sixty individuals" from February 1930 to April 1931. In a November 20, 1963, report, FBI attributed that figure to Joseph Valachi.)

The Bo Weinberg account, preserved in the article by Dixie Davis, appears to have been the source material for a 1940 discussion of the purge in Gang Rule in New York by Craig Thompson and Allen Raymond.

The authors related that Weinberg believed "scores of greasers were executed across the United States" on the same day Maranzano was killed. Thompson and Raymond did not let the story go at that, however. They explained, "Weinberg naturally did not know definitely that this was true, he knew only that he had performed his part in the liquidation."

A bit later they asserted that they had found confirmation for the Weinberg account:

"There has been, from several underworld sources, confirmation of the statement that September 11, 1931, was purge day in the Unione. The purge, as obviously bloody, abrupt and final as any ever arranged by a European dictator, left Luciano in command of the Unione in New York, without a dangerous disputant in sight."

The authors did not reveal the identities of their "several underworld sources." [4] Without knowing the sources, the statement's reliability cannot be assessed. It appears that Thompson and Raymond repeated the questionable Weinberg account while making an effort to give it additional credibility.

It appears that the first written account to refer to a post-Maranzano purge by the name "Sicilian Vespers" occurred in an Italian language draft autobiography prepared by mafioso Nicola Gentile during the 1940s.

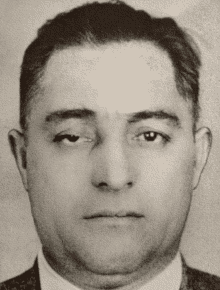

Gentile

Gentile had fled the U.S. to avoid prosecution on narcotics charges but then wanted to reenter the U.S. He provided his memoir manuscript to American authorities, probably in the years immediately following the end of World War II, in the hope of convincing them to drop the narcotics case and to allow his return. The effort was unsuccessful. But his manuscript became useful. It found its way through the Bureau of Narcotics to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. It was then translated into English and circulated among regional FBI offices and large-city police departments. It became the foundation for future investigations of organized crime.

Copies of the translation appear to have been gathered up and destroyed after Gentile's updated and revised autobiography was published in Italy in 1963. (Numerous references to the translation continue to exist in archived FBI documents.) At least one copy of the translated manuscript was preserved after passing into the possession of organized crime historians.

Siragusa

According to the manuscript, the killers of Maranzano - Jewish gunmen allied with Salvatore Lucania - and some associates, "hurried to telephones and informed the boys in various parts of New York advising them that they could start the purging operation. Almost immediately with that word there took place the slaughter of the 'Sicilian Vespers.' In fact, many of the followers of Maranzano were killed, who were stained with the most atrocious wickedness."

Gentile did not provide the names of the "many" who were killed or even indicate the number of victims. He also did not specifically define the period of time in which the purge occurred. He did, however, note that the killing was not confined to New York. He wrote, "No sooner did news of the death of Maranzano reach Cleveland that I and [John] Bazzano thought of eliminating Siracusa [or Siragusa] of Pittsburgh." [5]

The Palermo-born Giuseppe Siragusa, a Maranzano follower who took control of the Pittsburgh-area Mafia as Maranzano became U.S. boss of bosses in spring 1931, was in fact killed within a few days of the Maranzano assassination. He was found dead of gunshot wounds in his home, 2523 Beechwood Boulevard, in the late morning of September 13, 1931. [6]

In the 1940s, Kings County Assistant District Attorney Burton Turkus successfully prosecuted members of a Brooklyn-based murder gang known today as "Murder Inc." He benefited from the testimony of turncoat Abe "Kid Twist" Reles. In 1951, Turkus teamed up with journalist Sid Feder to produce the book, Murder, Inc.: The Story of the Syndicate.

That book asserted that at least thirty and as many as forty old-line mafiosi were purged following the assassination of Maranzano (called "Marrizano" here):

The day Marrizano got it was the end of the line for the Greaser Crowd in the Italian Society - the finish of 'The Moustache Petes'... For, in line with Lucky's [Lucania's] edict... some thirty to forty leaders of Mafia's older group all over the United States were murdered that day and in the next forty-eight hours!"

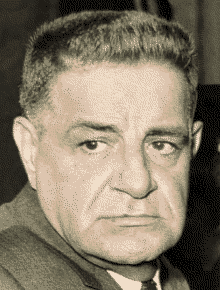

Turkus

This section, written in an authoritative manner by a former prosecutor of organized criminals, provided its readers with the sense that Turkus was revealing the conclusion of his own investigation. However, a paragraph later, he revealed that his story was based upon Dixie Davis's telling of Bo Weinberg's tale. Turkus mentioned no factual basis or independent research supporting the claim.

Apparently uneasy at having ninety people murdered within an hour, Turkus trimmed the Weinberg number of fatalities by more than half and expanded the timeframe to about three days (September 10th plus forty-eight hours). [7] As in the Thompson and Raymond retelling, these adjustments seem intended to improve the credibility of the story.

A few years later, Feder, then working with Joachim Joesten, repeated the purge legend for The Luciano Story. With Lucania the subject of the book, the authors emphasized that the purge conspiracy was led by Lucania:

Lucky was convinced. The ultimate and decisive purge of Mafia was decreed. The word went out that all Mustache Petes of any consequence had to go, not only in New York, but clear across the country. All the mob bosses pledged their co-operation. Almost simultaneously, on September 11, 1931, and within forty-eight hours thereafter, some thirty to forty Mafia executives were wiped out from coast to coast. So remarkable a feat of planning and execution was it that these thirty-odd homicides have never been linked... [8]

In the 1960s, Mafia turncoat Joseph Valachi penned his lengthy memoirs and gave a personal account of the Maranzano assassination aftermath. Valachi had served as a driver and gunman for Maranzano during the Castellammarese War of 1930-1931 and stayed on as part of the "palace guard" after Maranzano's selection as boss of bosses.

Valachi had been kept occupied in East New York on the day of Maranzano's assassination. That night, unaware of his boss's death, he returned to Manhattan. He was relaxing with friends at Charley Jones's Restaurant after one-thirty on the morning of September 11 when "a guy came in and he was looking us over. He left then a second guy came in and he was looking us over, he left and a third guy came and he was looking us over, that was enough for me."

Valachi

Valachi approached the restaurant owner, who he knew to be mob-connected. Jones told him simply, "Go home, Joe."

"That was all I had to hear," Valachi wrote.

He immediately returned to his apartment. "Then all of a sudden I hear a rustle of feet come up the stairs and I have a gun in my hand and I asked who is it and they said Buck, Johnnie D and Pete Muggin... So I opened the door and I saw the impossible all three of them had powdermarks on their necks and faces and none of them were hurt."

Valachi's friends told him they had been shot at by some other gangsters. Just then, Valachi happened to glance at the newspaper and saw that Maranzano and "Jimmy Marino" [Vincenzo LePore of the Bronx] had been murdered. "...and they killed one here and one there a few days later they found Sam Monaco in the Passaic River..." [9]

According to press reports and government documents, Vincenzo LePore was murdered two hours after Maranzano. While standing in the doorway of an Arthur Avenue barbershop as his daughters received a haircut, LePore was shot in the head and chest by gunmen in a passing automobile. LePore was said to be linked to the Maranzano organization, the future Bonanno Crime Family. [10]

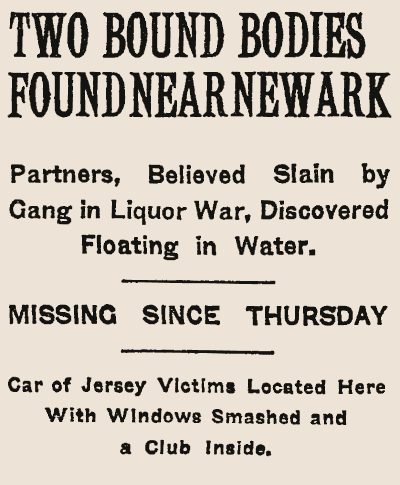

NY Times, Sept. 14, 1931

The body of racketeer Sam Monaco of East Orange, New Jersey, was found on September 14 floating in Newark Bay near the New Jersey Central Railroad bridge. His arms and legs were bound with adhesive tape and sash weights were tied to his leg. On the same day, authorities found the body of Monaco associate Louis "Babe Ruth" Russo of Newark, New Jersey, in the Passaic River near Kearny, New Jersey. He had been tied with clothesline. Like Monaco, he had sash weights attached to his body. Both men had been beaten and shot. Russo also suffered a severe blow to the head that crushed his skull.

Police learned that the two men were last seen alive on September 10, as they rushed off in Monaco's automobile. The car was found abandoned on West Forty-seventh Street in Manhattan. The press reported that the murders shattered a "truce that has existed in the local underworld for the past several months." Police noted that a third murder victim, unidentified but possibly connected with Monaco and Russo, was found in Orange, New Jersey, on September 10. [11]

Valachi hid out for a while but eventually got in touch with other underworld associates. He was called to meet with Vito Genovese, top lieutenant in Lucania's organization. Valachi asked about the recent shootings. "So he said whenever a boss dies all his faithful die with him..." [12]

Valachi could count only a few killings following the Maranzano assassination. But he knew of several other attempted killings and considered that, under slightly different circumstances, he himself might have been one of the Maranzano men killed.

In 1968, when author Peter Maas turned Valachi's memoirs into the book, The Valachi Papers, his subject's vague statement about "one here and one there" surprisingly became "an intricate, painstakingly executed mass extermination."

According to Maas, "On the day Maranzano died, some forty Cosa Nostra leaders allied with him were slain across the country, practically all of them Italian-born old-timers eliminated by a younger generation making its bid for power."

Maas's conclusion that forty killings took place in a day had murders occurring at a pace somewhere between Weinberg's ninety in an hour and Turkus's far more leisurely thirty-to-forty over three days. But the author still did not provide any support for his figure. Even the embellished Valachi quotations he used in his book counted up just three known murders. [13]

Donald Cressey took a quick look at the purge legend for his 1969 book, Theft of the Nation. He supported the view of Turkus, asserting that "some forty Italian-Sicilian gang leaders across the country lost their lives in battle" within three days of the murder of Maranzano.

But he then made a startling assertion. Without naming any of the victims, Cressey stated, "Most, if not all, of those killed on the infamous day occupied positions we would now characterize as 'boss,' 'underboss,' or 'lieutenant.'" [14]

Cressey provides source citations to support many of his claims. In this section of his book, he cites Turkus as support for the questionable notion that the purge was the final moment of the transplanted Sicilian-American Mafia and the birth of a new American crime syndicate. But he does not reveal what source prompted him to claim that all or most of forty murder victims were members of crime family leadership. (We also remain uncertain if he intended the term "lieutenant" to refer to the third-in-command consigliere or to the sub-leader position of capodecina/caporegime.)

Cressey's description

There may have been about thirty Mafia crime families in the United States at the time of Maranzano's assassination. The loss of forty leaders would have represented a near-complete beheading of the underworld network.

In April of 1971, shortly after the death of Joseph Valachi, New York Times reporter Nicholas Gage examined the memoirs of Gentile and found that they supported Valachi's 1963 testimony before the McClellan subcommittee of the U.S. Senate.

A Gage article, reprinted across the country, brought to a vast readership a couple of terms that had not been in common use to that point: "Sicilian Vespers" and "Mustache Petes." Gage also brought to widespread attention a supposedly authoritative estimate of the purge casualties:

"After the death of Maranzano, Gentile wrote, the younger Mafia leaders proceeded to eliminate many Mustache Petes in a single night of killings across the country that came to be called 'the night of the Sicilian vespers.' Gentile does not say how many old mafiosi were killed, but former United States Attorney General Ramsey Clark in his book, 'Crime in America,' put the figure at 40." [15]

Clark did make that statement, buried about a fifth of the way into his three-hundred-forty-six-page book, released a year earlier. He did not back it up with any sort of body count or source citation.

Clark

In a sensational (and inaccurate) passage, the former attorney general wrote, "Gang wars of the 1920's and 30's exceeded anything we have witnessed since World War II. Bosses with hundreds of gunmen held mass meetings in the days of Prohibition. On September 11, 1930, the day the self-proclaimed Boss of Bosses, Salvatore Maranzano, was assassinated, forty members of La Cosa Nostra died by gunfire." [16]

Gage's 1971 book, The Mafia is not an Equal Opportunity Employer, repeated the Gentile-Valachi-Clark-based statements of his New York Times article. [17]

By 1972 (the year The Godfather movie was released), when Gage released his book, Mafia, USA, he had begun to back away from the figure of forty purge murders. On what he called "purge day in the Unione," Gage abandoned the Clark estimate to state that "some thirty to forty executions were performed across the nation - a purge unprecedented in scope, precise in timing, and as bloody, abrupt, and final as any ever masterminded by a Stalin or a Hitler." (The "bloody, abrupt and final" description and comparison to Europe's dictators were obviously borrowed from the earlier Gang Rule in New York.) [18]

Even Gage's revised estimate of thirty to forty was off by at least one. He included in his total the murder of Gerardo Scarpato, owner of the Villa Tammaro restaurant on Coney Island, where "Joe the Boss" Masseria had been killed and where Salvatore Maranzano held a three-day banquet. (This error may have resulted from a careless reading of Gang Rule in New York, which described the Scarpato killing in the same section as the post-Maranzano purge.) But Scarpato was not killed on September 10, 1931, as Gage reported. Scarpato lived another year. His strangled body was found in an automobile on September 11, 1932. [19]

David Leon Chandler, who exhibited far more creativity than may be expected from a Pulitzer-prize-winning journalist, discussed the purge in his shockingly unreliable 1975 book, Brothers in Blood.

Chandler suggested that "The successful execution of Maranzano was the signal for the planned execution of some sixty Maranzano allies... The occasion has since become famous as Cosa Nostra's Purge Day and although no comprehensive death list has ever been compiled, there were at least eleven hits in the New York area alone."

The author marveled at the organizational skills required for what he viewed as a nearly simultaneous nationwide killing spree:

Implemented on a national scale, it must have required extraordinary preparation and communication. Each of the sixty victims must have been kept under surveillance to establish his daily pattern. For each of the sixty, a hit team had to be organized and gunmen chosen who wouldn't betray the plan. When Purge Day arrived, the hit teams had to be delivered to their target's area. A communications liaison must have been worked out to relay the go-ahead message from New York - that Maranzano had been killed - to each of the teams. Once their jobs were done, sixty teams had to escape.

Chandler calculated that at least three hundred men needed to be involved in the conspiracy. [20] It would have been an enormous operation, indeed, if it actually had occurred.

For their largely fabricated but inexplicably popular 1975 book, The Last Testament of Lucky Luciano, authors Martin A. Gosch and Richard Hammer created a lengthy quote and attributed it to Lucania. Through it, they disputed the legend of the purge:

Lucania

Every time somebody else writes about that day, the list of guys who was supposed to have got bumped off gets bigger and bigger. The last count I read was somewhere around fifty. But the funny thing is, nobody could ever tell the names of the guys who got knocked off the night Maranzano got his.

The authors claimed that Lucania did have a widespread purge planned but quickly called it off following Maranzano's assassination.

Gosch and Hammer reported that the only known victim of the "Night of the Sicilian Vespers" was Gerardo Scarpato. [21] As we've already discussed, Scarpato's murder would not qualify as a purge killing as it occurred in 1932.

Humbert Nelli decided to tackle the subject in his 1976 book, The Business of Crime. Nelli tracked as well as possible the birth of the "Night of Sicilian Vespers" legend. He acknowledged that three New York murders - Vincenzo LePore, Sam Monaco and Louis Russo - were likely related to Maranzano's assassination.

Nelli claimed he then conducted "a careful examination of newspapers issued during September, October, and November of 1931 in twelve large cities (Boston, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Baltimore, New Orleans, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, Kansas City, Denver, Los Angeles and San Francisco)."

Carlino

That research, he said, turned up only one killing that could have been part of a post-Maranzano purge, and it occurred in Denver. [22]

Nelli was referring to the murder of regional bootlegging boss Pete Carlino, of Denver, whose body was found outside of Pueblo, Colorado, on September 13, 1931. Carlino was shot three times. One slug tore open his head. Others struck him in the back, passing out through his chest. When found, the authorities estimated he had been dead two or three days. [23]

(Given the circumstances of Carlino's killing, as described by his relative Sam Carlino in the book, Colorado's Carlino Brothers, it appears at least as likely that Carlino was eliminated on orders of Maranzano, as part of his planned removal of underworld obstacles. [24])

Somehow, in Nelli's "careful examination," he missed all of the coverage given to Siragusa's murder in Pittsburgh.

He concluded that, "Contrary to the remembrances of 'Bo' Weinberg and Joseph Valachi, available evidence indicates that not ninety, or forty, or twenty, or even five murders were carried out across the United Stats in conjunction with, or as a consequence of, Maranzano's death." [25]

There is insufficient evidence to justify a claim of a carefully orchestrated nationwide purge of Maranzano allies following the Maranzano assassination on September 10, 1931. Certainly, nothing like the near-simultaneous killings suggested by Bo Weinberg (through Dixie Davis) and David Leon Chandler ever occurred.

The old principle "all politics is local" may apply here to underworld conflict.

It is likely that some regional Mafia factions held grudges after the Castellammarese War, as Maranzano allies moved into leadership positions and Maranzano opponents grudgingly accepted less important and less rewarding roles. These factions may have decided on their own to settle old scores upon learning that Maranzano was dead and no longer able to protect his followers. Such action required no meticulous planning or broad conspiracy, just news reports revealing that the boss of bosses was dead.

That was the situation, described by Gentile, that led to the demise of Pittsburgh boss Siragusa. It may also apply to the murders of New Jersey's Monaco and Russo (and perhaps to the unidentified New Jersey murder victim) - killings that occurred after a period of peace that roughly coincided with the reign of Maranzano as boss of bosses - to the murders of LePore in the Bronx and Carlino in Denver, as well as to the attempted murders of Valachi's three friends and the apparently planned but not attempted murder of Valachi.

Pollaccia

Some other violent changes in crime family leadership occurred during this period and may have been related in some way to the slaying of Maranzano. Gentile wrote about the murder of longtime New York mafioso Saverio Pollaccia, who had advised previous supreme Mafia leaders Salvatore D'Aquila and Joe Masseria. Sometime after Maranzano's murder, Pollaccia was taken by Vito Genovese to Chicago. Pollaccia reportedly was killed and buried near Chicago with help from Paul Ricca. Gentile said Pollaccia had committed some offense against Genovese, but he did not elaborate. [26]

Out in southern California, a wealthy Mafia figure named Joseph Ernest Ardizzone disappeared one month after Maranzano's death and was never seen again. Rumors indicated that Ardizzone was killed and disposed of by members of his own underworld organization. The reason remains a mystery. [27]

Some less violent leadership changes roughly coincided with the elimination of Maranzano. Though not murders, they may have contributed to the legend of the purge.

Scalise

In New York City, close Maranzano ally Frank Scalise in fall 1931 was removed from leadership of a powerful crime family (later known as the Gambino Crime Family) based in Brooklyn and the Bronx. He was replaced by Vincent Mangano. In Philadelphia, longtime boss Salvatore Sabella, who like Maranzano was born in Castellammare del Golfo, Sicily, stepped aside in 1931 so John Avena could take over. [28]

It is also possible that we are unaware of Mafia connections of a number of murders from the period. In his book On the Spot, historian Patrick Downey assembled a timeline of gangland hits from the later Prohibition Era. He identified some, including the murders of Giuseppe Mannino in Brooklyn on September 12, Joseph Meli in Manhattan on September 14 and Guglielmo Giuca in Brooklyn on November 17, as possibly linked to Maranzano. Other regions of the country may have had similar killings. [29]

Possibly, through a tortuous twisting and bending of our definitions, we could arrive at a total of killings, attempted killings, planned but not attempted killings and dramatic demotions that reached somewhere near the figures described in the purge legends. But it seems impossible that these could have resulted from a deliberate coordinated effort by a new generation of Mafia bosses.

1. "The Sicilian Vespers," New York Times, Feb. 8, 1874, p. 2; Bonanno, Joseph, with Sergio Lalli, A Man of Honor: The Autobiography of Joseph Bonanno, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1983, p. 39; Fentress, James, Rebels and Mafiosi: Death in a Sicilian Landscape, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000, p. 12.

2. Evola, Filippo, Lu Rebellamentu di Sichilia (1882 Palermo printing), Google Play Books, play.google.com; Verdi, Giuseppe, Verdi's opera Sicilian Vespers (Italian language version with English translation), Internet Archive, archive.org.

3. Davis, J. Richard, "Things I Couldn't Tell Till Now," Collier's, Aug. 5, 1939, p. 44.

4. Thompson, Craig, and Allen Raymond, Gang Rule in New York: The Story of a Lawless Era, New York: Dial Press, 1940, p. 374-375.

5. Gentile, Nicolo, Translated Transcription of the Life of Nicolo Gentile, unpublished manuscript translated by FBI, p. 113.

6. Joseph Siragusa Certificate of Death, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Department of Health Bureau of Vital Statistics, file no. 84600, registered no. 7395, Sept. 13, 1931; "Man is murdered by gunmen while family is absent," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Sept. 14, 1931, p. 1; "Yeast baron's three killers known, belief," Pittsburgh Press, Sept. 14, 1931, p. 1.

7. Turkus, Burton, and Sid Feder, Murder Inc.: The Story of the Syndicate, New York: Farrar, Straus and Young, 1951, reprinted Da Capo Press, 1992, p. 87-88.

8. Feder, Sid, and Joachim Joesten, The Luciano Story, New York: David McKay Co., 1954, reprinted Da Capo Press, 1994, p. 82.

9. Valachi, Joseph, The Real Thing, Second Government: The Expose and Inside Doings of Cosa Nostra, unpublished manuscript, Joseph Valachi Papers, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, 1964, p. 363-366.

10. Organized Crime and Illicit Traffic in Narcotics, Hearings before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, U.S. Senate, 88th Congress, 1st Session, Part 1, Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1968, p. 232-233; Flynn, James P., "The Criminal Commission, et al, New York Division," FBI report, file no. 92-6054-127, NARA record no. 124-10216-10235, Dec. 19, 1962, p. 52; McCoy, Leonard H., "La Cosa Nostra," FBI report no. 92-6054-740, NARA record no. 124-10205-10471, Aug. 21, 1964, p. 75; "Four witnesses indicted," New York Times, Sept. 12, 1931, p. 4; "Racket killing diary found; lists a judge," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Sept. 11, 1931, p. 1; Goheen, Joseph, "Gangs kill 4, 1 in offices on Park Ave.," New York Daily News, Sept. 11, 1931, p. 2.

11. "2 tied bodies afloat are gang victims," New York Daily News, Sept. 14, 1931, p. 37; "N.J. racketeers die in gang war," Asbury Park NJ Press, Sept. 14, 1931, p. 1.

12. Valachi, Joseph, The Real Thing, Second Government: The Expose and Inside Doings of Cosa Nostra, unpublished manuscript, Joseph Valachi Papers, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, 1964, p. 366-370.

13. Maas, Peter, The Valachi Papers, New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1968, p. 111-114.

14. Cressey, Donald R., Theft of the Nation: The Structure and Operations of Organized Crime in America, New York: Harper Colophon, 1969, p. 44.

15. Gage, Nicholas, "Mafioso's memoirs support Valachi's testimony about crime syndicate," New York Times, April 11, 1971, p. 51.

16. Clark, Ramsey, Crime in America: Observations on its Nature, Causes, Prevention and Control, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1970, p. 75. Clark placed the killing of Maranzano 364 days too early.

17. Gage, Nicholas, The Mafia is not an Equal Opportunity Employer, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1971, p. 32.

18. Gage, Nicholas, Mafia, USA, Chicago: Playboy Press, 1972, p. 112.

19. New York City Extracted Death Index, Kings County, certificate no. 18237, Ancestry.com; "Suspect slayers sought to avenge Masseria's death," Brooklyn Citizen, Sept. 12, 1932, p. 1; Passenger manifest of S.S. Saturnia, departed Naples, Italy, on May 21, 1932, arrived New York on June 1, 1932. Scarpato was apparently not in the U.S. at any time close to the killing of Maranzano. He obtained travel papers within a week of the Maranzano banquet in August, 1931, he and his wife traveled to Italy, and they did not return to the U.S. until June, 1932.

20. Chandler, David Leon, Brothers in Blood: The Rise of the Criminal Brotherhoods, New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1975, p. 160-161.

21. Gosch, Martin A., and Richard Hammer, The Last Testament of Lucky Luciano, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1975, p. 143-144.

22. Nelli, Humbert, The Business of Crime: Italians and Syndicate Crime in the United States, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1976, p. 181-183.

23. "Pete Carlino is found dead near Pueblo on Sunday," Greely CO Daily Tribune, Sept. 14, 1931, p. 1; "Trailed and murdered by a rival gang," Grand Junction CO Daily Sentinel, Sept. 15, 1931, p. 11.

24. Carlino, Sam, Colorado's Carlino Brothers: A Bootlegging Empire, Charleston SC: History Press, 2019.

25. Nelli, p. 182.

26. Gentile, Nicolo, Translated Transcription of the Life of Nicolo Gentile, unpublished manuscript translated by FBI, p. 115-116

27. "Search futile for Ardizzone," Los Angeles Times, Oct. 21, 1931, p. 28; "Missing California man is believed to be slain," Helena MT Independent, Oct. 19, 1931, p. 1; Tiernan, M.L., He Never Came Home: The Mysterious Disappearance that Devastated a Family, The Early History of Sunland, California, Vol. 5, Amazon Digital, 2014.

28. Flynn, SA James F., "The Criminal Commission; et al, New York Division," FBI report, file no. 92-6054-127, NARA no. 124-10216-10235, Dec. 19, 1962, p. 5; Morello, Celeste A., Before Bruno: The History of the Philadelphia Mafia, Book 1, 1880-1931, 1999, p. 98-99.

29. Downey, Patrick, On the Spot: Gangland Murders in Prohibition New York City 1930-33, Amazon Digital, 2017.