Article

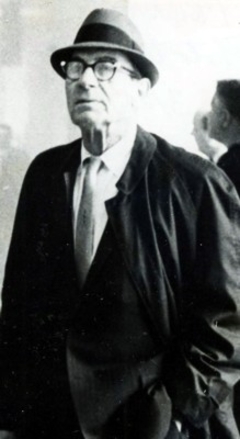

Frank Bonomo was a long-time member of the Bonanno Crime Family, who briefly may have served as a capodecina (group leader) during the late 1970s. Equally adept at avoiding the attention of law enforcement and the wrath of rivals, he survived the New York gangland "Banana War" and lived to the age of 86.

Frank Bonomo

Bonomo was born in the spring of 1901,[1] in Castellammare del Golfo, Sicily, to Francesco and Giovanna Lananna Bonomo. At eight years old, Bonomo and his family traveled to the United States, arriving at Ellis Island, New York, aboard the S.S. Liguria on March 27, 1909.

Aside from an arrest by the New York City Police Department around 1920 for carrying a knife, Bonomo managed to avoid the attention of the authorities through his early underworld career. Later information indicates that, like many others of the time period, Bonomo was an active bootlegger in partnership with other known Bonanno figures. His involvement might have been necessitated by the untimely death of his father, who was run down by a Brooklyn motorist two days before Christmas 1929.[2]

By the early 1930s, Bonomo was a "made" member of the primarily Castellammarese crime family headquartered in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Williamsburg. Bonomo and his first wife, Rose Cammarano, lived at 77 Powers Street in Williamsburg. Like many other known local Cosa Nostra members, Bonomo's legitimate employment related to the garment business. He served as a presser for the Kessler Coat Company at 498 Jefferson Street in neighboring Bushwick, Brooklyn.[3]

By 1942 Bonomo's first wife had divorced him for "running around with a wild group." In October of that year, he married Mary Biamonte in a ceremony held in Bayonne, New Jersey.[4] Through the 1940s, the new couple went through a succession of residences in the Bushwick and Williamsburg neighborhoods, eventually settling in Flatbush in 1948. In that year, Frank Bonomo became a naturalized U.S. citizen in the U.S. District Court of the Eastern District of New York.[5] A brother-in-law, Charles Cummo, and one Domenico LaBarbera, both residents of Bushwick, acted as witnesses on his behalf.[6]

Bonomo was a Mafia soldier and loan shark operating under the supervision of capodecina John "Johnny Burns" Morale in the Brooklyn neighborhoods of Bushwick, Williamsburg and Greenpoint. His loan sharking business grew through the 1950s and would continue for decades. All the while, he retained his connection to the local garment business, operating the D&S Sportswear company at 167 Troutman Street.

The Bonomo family moved in 1960 to 75 Nottingham Avenue in Valley Stream, Long Island. Bonomo brought his illicit enterprise with him to the new neighborhood, reaching out to area businesses with the help of his son Anthony in an effort to garner additional loan customers.

Frank Bonomo

The younger Bonomo, then in his mid-twenties and living in the Queens neighborhood of Elmhurst, had begun to take an active role in his father's underworld business. In October 1961, he successfully hooked the owners of a Huntington Station shoe store into a $1,000 loan charging 1.5% weekly interest. Anthony Bonomo was critically wounded by gunfire the following September; he briefly lingered before succumbing to the wounds on October 2, 1962. The circumstances that led to his killing are unclear. The gunman was later identified by a federal informant as "Sloppy Joe," but no motive ever was presented. The payments from the shoe store owners nonetheless continued.

Owing to increased attention placed by federal authorities on Cosa Nostra organizations, Bonomo showed up on the Federal Bureau of Investigation's radar in the fall of 1963. Electronic surveillance had been placed in the office of the Lane Thread Company, 207 Wilson Avenue in Bushwick. The business was operated by Frank LaBruzzo, a fellow Castellammarese and brother-in-law of crime family patriarch Joseph Bonanno. Bonomo's frequent trips to Lane Thread resulted in numerous conversations being intercepted by the FBI; over a one year period he was picked up by the Lane Thread bug on at least forty occasions. The discussions, often held solely between LaBruzzo and Bonomo but at times including Joseph Bonanno's son Salvatore, typically consisted of underworld gossip and gripes over the minor day-to-day troubles encountered in the course of business.

The conversations did serve, however, as a clear indicator that Bonomo held some degree of influence over the American Cloak and Suit Manufacturers' Association, referred to simply as "The Assocation" by those present on the Lane Thread interceptions. LaBruzzo and Bonomo were heard on multiple occasions to discuss the possibility of "kicking out" unspecified troublemakers in the association, and Bonomo mentioned personally attending meetings held by association members. Despite his connections to the garment industry, Bonomo also was continually harangued by Frank LaBruzzo for his failure to repay debts owed to Rosario "Sally Burns" Morale. "Sally Burns" was a Bonanno soldier and brother to John Morale, who had risen to the position of acting boss of the crime family. The situation resulted in Bonomo being temporarily "chased" from LaBruzzo's office until he settled the account.

Joseph Corozzo

By 1964, John Morale was demoted and laying low due to pressure both from federal authorities and members of his own crime family. Frank LaBruzzo replaced Morale as acting boss.[7] In April of that year, Bonomo met with LaBruzzo at Lane Thread, where the still-active federal bug recorded LaBruzzo commending Bonomo for being "a loyal Soldier for so long." Bonomo was subsequently placed in the regime headed by Gaetano "Smitty" D'Angelo, a major figure in the Brooklyn-Queens area.

As intra-family tensions between the Bonanno and DiGregorio factions increased, Bonomo threw his support to the DiGregorio side. He was identified by informants as an active co-conspirator in plots against the lives of several Bonanno supporters, including his former capodecina John Morale.

As the factional conflict grew, law enforcement stepped up investigations of those identified via the Lane Thread bug. Bonomo became a target of sporadic physical surveillance through the mid-1960s, at several points being sighted visiting with known Bonanno leaders and figures at Brooklyn's Pier 13.

In March 1966, Bonomo and nearly thirty others linked to the Bonanno Family were hit with subpoenas by a Kings County Grand Jury investigating the January 1966 Troutman Street shooting. After refusal on behalf of all those subpoenaed to answer questions, contempt proceedings were initiated[8] and dragged on through 1966 and into early 1967. During that time, Gaetano D'Angelo was busted down from his capodecina rank, and Bonomo was believed to have been assigned to a DiGregorio-appointed capodecina.

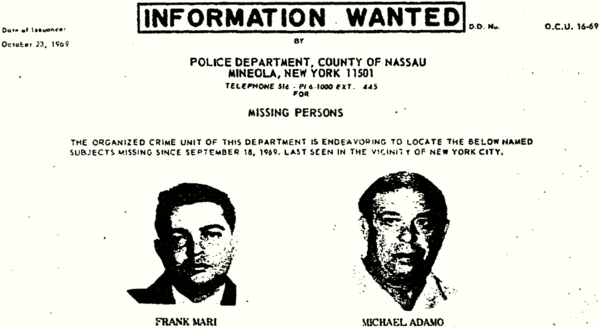

The Bonanno Crime Family continued to suffer intra-family violence and unstable leadership into the late 1960s. Paul Sciacca had claimed the organization's throne by 1969,[9] with Frank Mari as his underboss and Michael Adamo, a distant cousin to Bonomo, as the crime family's consigliere. Possibly owing to the blood connection with Adamo, Bonomo's standing in the new regime was enhanced, and he often served as Mari's driver.

Bonomo was acting in this capacity on September 18, 1969, when Mari was picked up from his residence and failed to return. He is believed to have been murdered by others in the Bonanno organization after making it known that he intended to take the top leadership spot. Michael Adamo, allegedly party to Mari's ambitions, also was marked for death and disappeared the same day.[10] One week after the men went missing, Bonomo was confronted by the FBI and admitted picking up Mari on the day of his disappearance, dropping him off in the vicinity of West 38th Street in Manhattan with instructions to return for Mari at that location the following day. Aside from this admission, no details linking Bonomo to the actual disappearance emerged.

Frank Mari and Michael Adamo missing.

Paul Sciacca stepped down after a brief tenure as boss, and a triumvirate was installed atop the crime family. Bonomo remained a soldier and, now retired from his legitimate interests and collecting Social Security, spent his days frequenting the Aqueduct Raceway, card games in Manhattan and social clubs and coffee shops along Knickerbocker Avenue in the old Bushwick neighborhood. He occasionally sold clothes to patrons of the various local establishments, and had another son allegedly helping with various other interests, including an apparent business contract with area lighting companies.

Around 1975, Frank Bonomo expanded his crew of young associates, bringing Peter Zuccaro under his protection. Zuccaro operated a body shop in Brooklyn's East New York neighborhood, His grandfather was previously associated with the Bonanno group and had come into conflict with Joseph Corozzo and John Setaro, associates responsible to Gambino Crime Family member Anthony "Tony Lee" Guerrieri. A sit-down was held between Bonomo and Guerrieri, and the issue was smoothed over. Zuccaro was subsequently put on record with Bonomo for protection. According to court testimony given by Zuccaro years later, Bonomo was an easygoing superior, never demanding regular tribute payments from his men, although Zuccaro would frequently pay respects to his superior in the form of clothes, jewelry and tires for Bonomo's vehicle.

Frank Boccia

Frank Bonomo's rank during this period of Bonanno Crime Family history is unclear. Peter Zuccaro claimed that Bonomo was a capodecina through the mid-to-late 1970s.[11] In conflict with this assertion are details provided to the FBI by a newly made member of the Bonanno Family who was also an active informant. In January 1979, this member source identified Bonomo as one of thirteen men reporting to Angelo Salvo. Salvo, another old-timer only a few years younger than Bonomo, was born in Willisville, Illinois, but by the 1930s resided in New Jersey. By 1979, he controlled crime family operations there while also maintaining a crew of soldiers in New York.

Regardless of his rank, Bonomo is identified as instigating the November 1979 murder of Settimo Favia. A resident of Queens, Favia was employed in the pizzeria business and also had the reputation on Knickerbocker Avenue of being a heavy gambler. He sealed his fate after verbally abusing Bonomo for reasons unknown.[12] In response Bonomo requested and received permission for Favia's murder and assigned his crew of young associates to carry out the hit.[13] Favia was ambushed outside of his home by a hit team comprised of Frank "Geeky" Boccia, Pasquale Andriano, Robert Santora and Peter Zuccaro. Boccia fired the shots that killed Favia. The group then sped from the scene in a stolen vehicle driven by Zuccaro.

Frank Bonomo was more or less a non-entity in Bonanno Family affairs by the early 1980s.[14] Of the young associates he commanded in the late 1970s, Pasquale Andriano had been murdered,[15] Peter Zuccaro and Frank Boccia had been indicted and subsequently imprisoned for armed robbery,[16] and the others had transferred to the Gambino Crime Family. Briefly in New York after being called to testify in a Federal case, Zuccaro was approached behind bars by Bonanno Family heir apparent Joseph Massino and informed that he had been given to the Gambino Crime Family as well.

The extent of Frank Bonomo's activity in his waning years remains unknown. He died of natural causes on or around December 27, 1987 in Longwood, Seminole County, Florida.[17]

Notes

[1] Social Security Death Index; Petition for Naturalization

[2] "Motorist held for homicide as victim expires," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Dec. 27, 1929. The motorist, Charles D. Eve, struck four persons with his car on Dec. 23 at Eastern Parkway and Howard Avenue. Eve was reportedly intoxicated at the time and had a record of nine convictions on drunken driving charges. Bonomo's injuries initially required the amputation of his left leg. Surgeons could not repair his internal injuries, which proved mortal.

[3] New York State Census of 1925, U.S. Census of 1930, U.S. Census of 1940. The 1925 state census found Frank and Rose Bonomo living on North Seventh Street in Brooklyn with son Frank Jr., 3, and daughter Jennie, six months old. Bonomo reported he was working as a chauffeur. At the time of the 1930 census, Bonomo and his wife Rose lived at 172 Maujer Street, Brooklyn, with son Frank Jr., 8, and daughter Jennie, 6. Bonomo reported that his occupation was taxi driver. For the 1940 census, Bonomo claimed he earned $400 as a presser in the ladies coat factory during the year 1939. The 1940 census records show Bonomo living at 77 Powers Street in Brooklyn with wife Rose, 34, son Frank Jr., 17, daughter Jennie, 15, and son Anthony, 7.

[4] Marriage License #20691. City Clerk's Office. Bayonne, New Jersey.

[5] At the time of his naturalization, Bonomo lived at 832 E. 46th Street in the East Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn.

[6] Declaration of Intent #345152, United States District Court, Eastern District of New York, 1946; Petition for Naturalization #461424, United States District Court, Eastern District of New York, 1948; Certificate of Naturalization #C-6 724180, United States District Court, Eastern District of New York, 1948.

[7] Evans, C.A., "La Cosa Nostra," FBI memorandum to Mr. Belmont, April 24, 1964, FBI file 92-6054-633, NARA record 124-10286-10363; Evans, C.A., "Criminal Intelligence Report," FBI memorandum to Mr. Belmont, May 20, 1964, FBI file 92-6054-641, NARA record 124-10287-10190. The reports by Evans indicate that information on Labruzzo's elevation to boss was obtained through "highly confidential sources" close to Labruzzo and Buffalo crime boss Stefano Magaddino. These sources were electronic listening devices. Magaddino was heard telling colleagues that Joseph Bonanno endorsed Frank Labruzzo as new boss and Salvatore "Bill" Bonanno as consigliere in March 1964. The regime change was confirmed by overheard Labruzzo comments. According to the FBI documents, Labruzzo met formally with crime family lieutenants in April 1964 and said he had not yet fully assumed control of the crime family.

[8] "9 Bananas pals draw 30 days, fine in clamp." New York Daily News. July 8, 1966; "Court sentences 9 in a Mafia battle." The New York Times. July 8, 1966.

[9] O'Neil, Robert G., "La Cosa Nostra," FBI report, Oct. 20, 1967, FBI file 92-6054-2175, NARA record 124-10277-10308, p. 48; O'Neil, Robert G., "La Cosa Nostra," FBI report, Sept. 26, 1968, FBI file 92-6054-2456, NARA record 124-10290-10437, p. 28; SAC New York, "La Cosa Nostra," FBI memo, April 4, 1969, FBI file 92-6054-2618, NARA record 124-10297-10105, p. 5. The FBI learned in June 1967 that Paul Sciacca had been recognized as Bonanno Crime Family boss on a temporary basis, while the Commission attempted to force Joseph Bonanno into a full retirement. A month later, the FBI reported that the situation was uncertain, and some continued to believe that either Joseph Bonanno or Gaspare DiGregorio retained the boss title. In August, a source told the FBI that Sciacca had the backing of Joseph Colombo, boss of his own crime family. The source felt there was little hope for compromise between the Sciacca faction and Bonanno loyalists. A different source reported that some members of the Bonanno Crime Family had been absorbed into the Gambino Crime Family during the factional struggle. A source informed the FBI that on Oct. 31, 1967, the Commission gave its formal approval to Sciacca as boss, though Bonanno loyalists continued to resist. Early in 1969, the FBI identified Sciacca as Bonanno Crime Family boss and Frank Mari as underboss.

[10] Grutzner, Charles, "2 missing men believed to have been slain," New York Times, Oct. 4, 1969, p. 4; Pileggi, Nicholas, "The story of T," New York Times Magazine, March 29, 1970, p. 13.

[11] Zuccaro identified other Mafia captains who turned out to have been merely soldiers.

[12] Blumenthal, Ralph. Last Days of the Sicilians. Random House Value Publishing, 1988, p. 11-12. Blumenthal described an anonymous letter sent to the Queens office of the FBI. The letter indicated that Settimo Favia lost a great deal of money gambling in the back room of the Café del Viale on Knickerbocker Avenue. Mafioso Cesare Bonventre approached Favia with an offer to cancel his debt if he would help transport a shipment of drugs from Italy to the U.S. Favia angrily refused the offer, the letter said.

[13] According to reports, Bonomo was directly involved in setting up Settimo Favia's murder. He called Zuccaro and others to a social club on Knickerbocker Avenue to give them the order and drove the group to the victim's neighborhood while formulating the plan.

[14] Bonomo received a "cut" from two armed robberies committed by Zuccaro and associates. The first occurred on July 29, 1980, in Queens, when Zuccaro, Frank Boccia, Joseph Cavalcante and Andrew Curro stole $310,000 from an IBI Security Services Truck. Then on Dec. 26 of that year, another IBI Security Services Truck was robbed of $750,000 in Brooklyn.

[15] Peter Zuccaro testimony, United States v. Charles Carneglia (08-Cr-76), U.S. District Court, Eastern District of New York, 2009.

[16] Fahim, Kareem, "Court officers turn out for trial in the case of a colleague who was killed in '76," New York Times, Feb. 4, 2009; Marzulli, John, "Rat sticks it to Teflon Don!" New York Daily News, May 24, 2012; Brick, Michael, "Mobster guilty of racketeering, but not murder," New York Times, May 12, 2007; Capeci, Jerry, "Prosecutors may have more Junior Gotti ammunition," New York Sun, April 19, 2007. Facing capital punishment or life-in-prison sentences for murders and drug crimes, Peter Zuccaro became a government witness against some of his former underworld colleagues. Zuccaro assisted in the government's partially successful 2007 case against Gambino Crime Family capodecina Dominick Pizzonia. He testified in the 2009 trial of Gambino Crime Family member Charles Carneglia. Last year, he testified in the murder trial of reputed Gambino Crime Family associate John Burke.

[17] Social Security Death Index.

Additional Sources

- Blumenthal, Ralph. Last Days of the Sicilians. Random House Value Publishing, 1990.

- DeStefano, Anthony. Mob Killer: The Bloody Rampage of Charles Carneglia, Mafia Hit Man. Pinnacle, 2011.

- FBI File 92-7720.

- Immigration and Naturalization File #A-5 346 740.