Salvatore Piscopo

Salvatore Piscopo was a longtime member of the Los Angeles Crime Family and a close associate of mob legends Johnny Roselli and Jimmy Fratianno. Piscopo ran a large-scale gambling operation for the mob. Although he never rose higher than soldier, Piscopo had a front row seat to organized crime's infiltration of the movie industry and the gang wars that boiled over in Southern California in the 1940s and 1950s. He died in 1977.

If Piscopo is remembered at all today, it's because Jimmy Fratianno fingered him as the individual that exposed Johnny Roselli's secret identity to federal authorities. But the full extent of Piscopo's cooperation with the Federal Bureau of Investigation has remained unknown until now.

Recently declassified FBI documents linked to Piscopo, reveal he was the best source of inside information about La Cosa Nostra in Southern California in the early 1960s. [1] Before other informants like Frank Bompensiero and Fratianno ever told federal authorities anything about the inner workings of the Los Angeles Crime Family, Piscopo was divulging Mafia secrets going back decades.

Much of the data in this article comes from Piscopo's interviews with federal agents between 1963 and 1965, though he cooperated until at least 1969. The interviews likely represent only a fraction of his total interaction with the FBI.

Not everything Piscopo said turned out to be accurate, but what he revealed about the basic structure and rituals of La Cosa Nostra would largely substantiate Joseph Valachi's testimony at the McClellan Hearings.

Early Years

Salvatore Louis Piscopo was born December 10, 1893, in Naples, Italy. His parents were Vincenzo Piscopo and Grazia Battistrada. He left school after the eighth grade. Piscopo came to the United States in 1921, arriving at Ellis Island. [2] He worked on the ship Regina d'Italia as an "ordinary seaman" on the passage over. He was twenty-seven years old. He became a naturalized American citizen in 1938. [3]

Regina d'Italia

Piscopo was five feet six and a half inches tall and had a medium build. He had brown eyes, dark hair and a dark complexion. He had a scar on his right hand and another over his left eye. [4]

Piscopo settled in New York City. He met a young woman named Evelyn Gann, the daughter of Russian/German immigrants. She worked as a store clerk. [5] Piscopo and Gann apparently married soon after they met, though their marital status remained uncertain for a dozen years more.

Two marriage certificates exist for them. The first was issued in July 1922 at Manhattan. [6] However, an FBI source who knew Piscopo in the 1920s said he lived "common-in-law" with Gann at the time. The source added that Piscopo and Gann didn't formally marry until sometime in the 1930s after their children were born. [7]

Nonetheless, they presented themselves as a married couple on the 1930 United States Census. [8] Piscopo indicated his age at first marriage was twenty-seven while Gann answered age eighteen, which was consistent with a marriage in 1922.

Piscopo

However, a second marriage certificate was issued for them on October 15, 1934, in Los Angeles. Piscopo and Gann were married by a justice of the peace. The best man was mobster Michael Moro. [9] While this was Gann's first marriage, the marriage certificate indicated that it was, in fact, Piscopo's second marriage and that he was a widower. It turns out Piscopo was married in Italy and had a child before he ever came to the United States. [10]

(Piscopo indicated on the 1930 census that he immigrated to the United States in 1924. In reality, he had been in the country since 1921 and had already "married" Gann in New York City by 1922.)

Piscopo had three children. Anna (or Nanilla), the eldest child, was born in Naples, Italy in 1921. She was the child of Piscopo's first marriage to Concetta Ferrera. [11] Anna remained in Italy with her mother when Piscopo traveled across the Atlantic. In 1935, she immigrated to the United States and moved in with her father and stepmother in Los Angeles. [12]

A son, William George, was born in Los Angeles in 1924. [13] He was the first child of Piscopo and Gann. By this time, Piscopo had become a good friend to Johnny Roselli. Roselli was named the boy's godfather. [14]

A third child, Evelyn Helen, was born in 1928 in Los Angeles. [15]

L.A. Times

William Piscopo took a distinctly different life path from his father. The son trained to be a Navy pilot. During World War II, he served abroad the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Bennington. He was credited with three kills at the Battle of Iwo Jima. He graduated from the University of Southern California with a degree in physical education. In 1950, Lt. Piscopo died during a practice bombing run with his Naval Reserve squadron at the Navy Auxiliary Air Station in El Centro, California. A fragment from his own bomb struck his low-flying plane and brought it down. [16] Piscopo was buried at Calvary Cemetery in Los Angeles. [17] His mother, Evelyn Gann Piscopo, who died in 1957, was buried nearby. [18]

Salvatore Piscopo owned his own home in Los Angeles. In 1930, it was valued at $10,500. By 1940, he had moved down the street into a different home valued at $4,500. [19]

Piscopo had an arrest record in Los Angeles going back to 1926 for gambling, suspicion of robbery and assault with intent to commit murder. The Los Angeles Police Department described him as a "bookmaker, tout, lay-off man, and a gambler." [20] On the street, he was known as "Luigi Merli" and "Dago Louie." Piscopo hung out at the Villa Capri, a popular restaurant for celebrities and gangsters. [21]

Piscopo was arrested at home around 1927 on a bootlegging charge. During the raid, his young son William told the police searching the house where to find hidden whiskey.

In March, 1929, Piscopo was arrested in New York City for the murder of Pasquale Longo. The murder took place seven years earlier in 1922 in Little Italy, Manhattan. [22] Fleeing from this murder charge was probably what first brought Piscopo to California. A source who knew Piscopo in Los Angeles in 1924 stated that it was common knowledge that he was "wanted on a homicide charge in New York City." [23] Piscopo was later acquitted at trial.

Piscopo functioned as Roselli's "secretary" in the 1920s. [24] People who knew both men at the time considered them best of friends. It was then that Piscopo learned Roselli's real name, his birth in Italy and his childhood in Massachusetts. He met Roselli's mother and siblings. Roselli eventually used Piscopo as a courier to secretly deliver money to his family. Piscopo would do anything Roselli told him to do.

Fratianno

Piscopo gave his occupation variously as a salesman of "wholesale electric appliances," a salesman and cook at a restaurant on Sunset Boulevard, and a "clothing jobber." He worked as a "union representative" in the "theatre" industry making as much as $1,600 a year. [25] [26] [27] [28] Piscopo was running a large gambling and bookmaking operation by this time. He was considered one of Roselli's lieutenants.

By the 1930s, Roselli had become a powerful figure in the motion picture industry. One source told the FBI that Roselli got Piscopo his union job. [29] Harry Cohn, the president of Columbia Pictures, knew Piscopo by sight and described him as Roselli's "henchman." [30] Roselli was later imprisoned for his part in the mob's extortion scheme; Piscopo was never charged.

Salvatore Piscopo was the first gangster Jimmy Fratianno met after he relocated to California from Ohio. Piscopo was a bookmaker and had befriended Fratianno after he opened his own book. Piscopo introduced Fratianno to Johnny Roselli and crime boss Jack Dragna, and set him on the road to mob membership.

In 1947, Piscopo and Fratianno were inducted into the Los Angeles Crime Family in the same ceremony. Fratianno would later testify against his mob associates and write a popular memoir about his criminal life. Piscopo appeared as a minor figure in Fratianno's book.

Fred Sica

Piscopo was arrested on Feb. 7, 1950, with brothers Joseph and Fred Sica, and charged with assault with a deadly weapon. The Sica brothers, originally from New Jersey, worked with members of the Italian and Jewish underworld. Piscopo and the Sica brothers were suspected of dynamiting the home of gangster Mickey Cohen with "between 20 and 30 sticks of dynamite." [31] Cohen was a Jewish rival of the the Los Angeles Crime Family. The blast ripped a hole in the side of Cohen's home but did not kill the gangster.

Piscopo and Cohen had a running feud after Cohen robbed one of his betting parlors of more than $32,000. [32] Because Piscopo was connected to Johnny Roselli and Jack Dragna, a sit-down was needed between Italian and Jewish gangsters to settle the matter. Cohen was able to keep the money but was ordered by Benny Siegel to return Piscopo's stolen "stickpin" because it was a family heirloom. According to Cohen, Piscopo had a "real Italian accent and way of expressing himself."

Piscopo opens up

Salvatore Piscopo began to share confidential information with the FBI in May of 1963. This was six months before Joseph Valachi became the first inducted member of La Cosa Nostra to publicly testify at McClellan Committee Hearings in Washington, D.C.

According to the FBI, Piscopo was persuaded to cooperate based on information supplied by his close associate Nick Simponis. Simponis was a Greek gambler who operated a casino in Cabazon, California. The Los Angeles Crime Family secretly owned a piece of it. Simponis himself began to share confidential information with the FBI in 1962, about a year before Piscopo. Simponis was assigned the informant symbol code "LA 4412." [33]

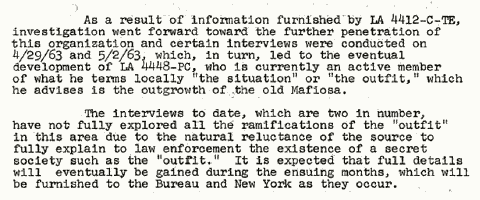

The FBI said the confidential information "furnished" by Simponis led to "certain interviews" and the "eventual development" of Piscopo as a source. [34] To protect his anonymity, Piscopo was assigned the informant symbol code "LA 4448." Any confidential information supplied by Piscopo showed up in an FBI report under this symbol code.

Piscopo was 'LA 4448'

According to the FBI, informant "LA 4448" and Johnny Roselli were cousins. [135] Piscopo and Roselli often claimed, before it was disproven, that they were cousins. [136] FBI documents show "LA 4448" was the source that revealed Roselli's true identity to the FBI. [137] The Last Mafioso and All American Mafioso confirm Piscopo was the individual that gave up Roselli.

Just before Piscopo began to talk, the FBI planted a listening device in a building controlled by Simponis and frequented by Piscopo. (This was likely done without Simponis' knowledge. The FBI often secretly planted bugs inside the homes and businesses of confidential informants to confirm their information and to record conversations with their associates.) According to the FBI, the listening device was used "in connection with Piscopo in its efforts to further penetrate into the Italian underworld and the set up of the various families." [35]

There is at least one transcript available revealing recorded conversations between Piscopo and Simponis. [36] The FBI may have developed a lead from its eavesdropping operation to flip Piscopo. (There is no evidence in the available FBI documents that Simponis ever suspected Piscopo was an informant.)

According to "All American Mafioso: The Johnny Roselli Story," Piscopo turned FBI informant in "late 1963" after he ran afoul of the Internal Revenue Service for failure to file income tax returns. (FBI documents indicate he was sharing Intel by May, 1963). The FBI was allegedly tipped off about his tax problems by the "security staff" at the racetrack frequented by Piscopo. Piscopo was a heavy gambler and had gotten into some trouble over it. In return for his cooperation, the FBI helped Piscopo square away his tax problems. Piscopo "figured he could gain a bit of protection by parceling out a little harmless information." [37] Simponis, a regular at the same racetracks as Piscopo, may have heard about his tax troubles and alerted the FBI.

The Interviews

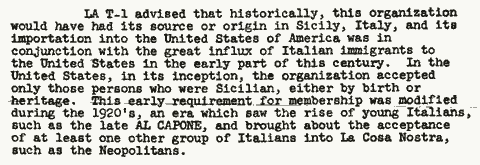

Piscopo told federal agents the organization originated in Sicily, and came to the United States with immigrants at the turn of the 19th Century. [38] In Los Angeles, the organization was called the "Situation" or the "Outfit" by its members. Initially, the organization only accepted individuals of Sicilian birth or ancestry but things changed in the 1920s when Neapolitans like Al Capone became members. However, Sicilians remained the dominant group. Piscopo said Neapolitan mobsters like himself couldn't "really hope to rise to the same positions of responsibility and leadership" as Sicilians. [39]

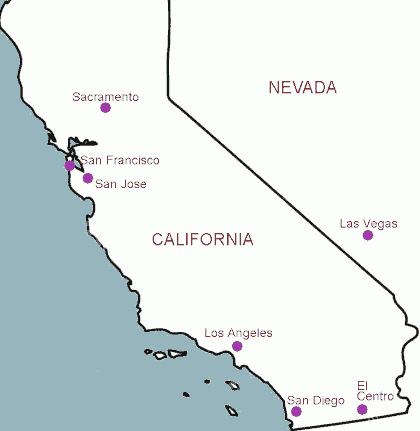

According to Piscopo, the organization was "nation-wide" with "families" located in major cities in the northeast, midwest and western United States. He said there was one family in Southern California that stretched from Los Angeles to San Diego. He said there were Mafia groups in San Francisco and San Jose but he didn't know much about them.

Each crime family was led by a boss. Piscopo said all bosses enjoyed the same "prestige" regardless of their family size or wealth. Each boss had a "lieutenant" or "sub-boss" who oversaw the operation of the crime family on his behalf. Under the lieutenant were the "caporegimes" who controlled the soldiers in the various groups that make up a crime family.

The boss relayed orders to the caporegimes through the underboss. Caporegimes would then pass orders onto the soldiers. Piscopo said no one had the right to question the order of a boss. Refusing an order could result in death. A soldier had to inform his caporegime about his whereabouts at all times.

Piscopo said bosses were supposed to retire at age 65, although this didn't always happen. The requirement was designed to allow younger men to be promoted within the organization without anyone having to resort to violence to make it happen. After a boss retired, he continued to receive a small portion of the profits generated by the crime family. The new boss was usually promoted from the ranks of the caporegime. According to Piscopo, caporegimes were the real power in the crime family. He said sometimes there is violence amongst the caporegimes when they vie for power to replace the boss.

In addition, each crime family had an advisor called a consigliere. According to Piscopo, the importance of the consigliere differed from family to family. Sometimes it was a "minor" position and other times it was very powerful.

He said all the crime families in the United States answered to a "Commission" composed of the bosses of the leading families. He said there were between five to eight bosses on the Commission. He said some consiglieres were on the Commission and had attended the mob meeting at Apalachin in 1957. Piscopo said the Los Angeles Crime Family wasn't on the Commission but its interests were represented by the Lucchese Crime Family.

Because of the fallout from the police raid at Apalachin, Piscopo said such large mob gatherings were discontinued for security purposes. He said the bosses of the smaller crime families no longer had regular direct contact with the Commission bosses and only met with them in exceptional cases. [40] Piscopo noted that the lack of direct contact made communication difficult.

Piscopo told federal agents that the organization in Southern California had never been "highly organized" like New York or Chicago. [41] There were three primary reasons why LCN never dominated organized crime in Los Angeles like in other cities.

First, the Los Angeles Crime Family was never very big. Piscopo said it had about twenty-five members in 1963 and many were old and inactive. It hadn't inducted any new members in years.

Second, multiple and competing "investigative agencies" overlapped Los Angeles County making it difficult for members "to establish any connections with law enforcement which would be of enduring value." Piscopo said organized crime can only prosper if criminals have the partial cooperation of law enforcement.

And finally, the disreputable behavior of former boss Jack Dragna also hurt the organization. Piscopo stated that the crime family suffered a "loss of face" after Dragna was "caught in a compromising position with a teenage girl." It appears that Piscopo was referring inaccurately to a widely publicized affair with model Annette Eckhardt that brought Dragna into court on morals charges in 1951. According to published accounts, Eckhardt was not a teenager but twenty-three years old at the time of her relationship with Dragna. The details of their affair were documented by police use of a listening device, secretly installed in Eckhardt's bedroom. [42]

Federal authorities would try to use the morals case against Dragna as a pretext to deport Dragna for entering the country illegally. Dragna died before the case was settled.

According to Piscopo, the power of the organization reached its zenith under Jack Dragna. Under his successor Frank Desimone, however, the organization had "declined steadily in strength, influence, and activity." It engaged in some loan sharking and gambling activities, but overall it was quite inactive. [43]

Initiation

To become a "made" member of the organization, Piscopo explained that an individual would first have to be recommended by an existing member. [44] The prospect would have to be seen as having the potential to be a good "brother." Members would observe the prospect and slowly expose him to the activities of the organization. Eventually, the prospect would be asked to prove himself by killing someone. (Piscopo never admitted to participating in a murder.)

Because Los Angeles hadn't made any new members in years, some prospects had been involved in many murders without being inducted. Piscopo alleged one unnamed prospect had been involved in twenty-three killings for the organization while another had been involved in eight. In 1963, Piscopo said Sam Sciortino had been proposed for the last three years but still hadn't been "made." [45]

Sciortino

Piscopo said initiations were sometimes held at a winery controlled by the organization. The boss would lead the induction ceremony and would sit at the head of the table. Seated next to him was the underboss, followed by the consiglieri, the caporegimes and the soldiers. At the end of the table, in the lowest level of prominence, were the individuals waiting to be inducted. Mobsters were required to leave any weapons on the table before they could be seated for the ceremony.

A prospective member had his finger pricked with a pin by his new caporegime and then the caporegime would draw blood and suck it. (Los Angeles Crime Family member-informants Jimmy Fratianno, who was inducted in the same ceremony as Piscopo, and Frank Bompensiero, both described their induction ceremonies and neither mentioned the caporegime sucking the wound. It's possible the federal agent misunderstood what Piscopo said.) [46]

The boss explained to the new member how he had to show complete obedience and loyalty to the organization, and how he always had to keep his mouth shut. Membership was meant to stay secret. The boss then stated, "We are all brothers. I will kill for you and you will kill for me. We avenge insults against each other."

The new member would be introduced to other members individually after the ceremony, using the phrase, "He is one of us." [47]

Rules

Piscopo learned more rules as time went on. He was told that any contact with out-of-state mobsters had to be first made through the boss. Piscopo said the boss would then pass on requests or assignments to the underboss who would then forward them to the caporegimes. [48]

If another LCN group tried to move into the established "territory" of the Los Angeles Crime Family, Piscopo said "New York would be immediately contacted and the group would have to move out immediately or be exterminated."

A soldier could transfer between two crime families if he had the permission of both bosses. Piscopo gave the example of former Los Angles Crime Family member Charles Battaglia who transferred his membership to the Arizona group led by Joseph Bonanno. (Battaglia would later regret the transfer.) [49]

Charles Battaglia

On April 25, 1965, Piscopo told federal agents that Louis Tom Dragna said Charles Battaglia, a former Los Angeles Crime Family member who had transferred his membership to Joseph Bonanno's group in Tucson, Arizona, was "slated to go." [138] Battaglia transferred out around 1960 because he disliked boss Frank Desimone. [139] Dragna never told Piscopo who wanted Battaglia dead or why.

In September 1967, Charles Battaglia told Piscopo he wanted to transfer his membership back to the Los Angeles Crime Family. [140] Desimone, his former nemesis, had died a month earlier clearing the way for Battaglia to return. Battaglia wanted Piscopo to arrange a meeting with his caporegime Angelo Polizzi in order to facilitate the transfer.

Crime Family Administration

Adamo

Palermo

Cascio

Tripoli

Piscopo broke down the LCN power structure in Southern California in the early 1960s. This kind of information was valuable because it helped the FBI to allocate resources on the appropriate targets. Piscopo said Frank Desimone was boss. Desimone had replaced Jack Dragna after he died in 1956. Desimone's underboss and consigliere were Nick Licata and Thomas Palermo. Angelo Polizzi, Joseph Adamo, Joseph Dippolito and Joseph Giammona were caporegimes. [50]

Piscopo said Thomas Palermo had never been a particularly active member of the crime family. His brother-in-law and fellow member John Cascio owned a winery that was sometimes used for meetings and initiation ceremonies. [51] Piscopo said Joseph Giammona had no soldiers assigned to him because he was old and sick.

The Los Angeles Crime Family had a crew based in San Diego led by Joseph Adamo. Frank Bompensiero used to be the caporegime until he was busted down to soldier by Desimone. Bompensiero was succeeded by Anthony Mirabile. Adamo took over in 1958 after Mirabile was killed. [52] Piscopo said Adamo functioned like an underboss for Desimone in San Diego in the same way as Licata functioned as his underboss in Los Angeles. According to Piscopo, Licata and Desimone rarely visited San Diego.

Piscopo belonged to the crew of Angelo Polizzi. Other members of the crew included Dominic Tripoli, Anthony Mangione and Joseph "Danny Wilson" Iannone. [53] According to Frank Bompensiero, Piscopo would sometimes host mob meetings in his home. [54]

Piscopo said Los Angeles Crime Family member Arthur DiMaria had lived in Las Vegas since the 1940s. [55]

Former consigliere, Tom Dragna, lived in Las Vegas. Dragna had fallen out of favor with the new leadership and was mostly retired. [56] Piscopo said that "resentment" had built up among members during the last few years of Jack Dragna's time as boss as it became apparent that Jack and Tom Dragna were "grooming" Tom's son Louis Tom Dragna for "leadership" in the crime family. [57] This didn't sit well with other members because Louis Tom Dragna had never "proved" himself. Piscopo said he "had no particular abilities." [58]

Tom Dragna

Louis Dragna

Bompensiero

After Jack Dragna died in 1956, the resentment spilled out into the open and the new leadership decided to hold a "trial" for Tom Dragna and his son. They were found guilty and were sentenced to death. According to Piscopo, only the intervention of New York crime boss Thomas Lucchese saved their lives.

According to Piscopo, Desimone and Licata were still concerned about Louis Tom Dragna's ambitions into the 1960s. Joseph Dippolito, Dragna's caporegime, was under instructions to keep on an eye on him and to report back any suspicious activity.

Piscopo said Frank Bompensiero and Johnny Roselli had been close friends since the 1920s. [59]

Roselli used to be a member of the Los Angeles Crime Family before he transferred to Chicago. Bompensiero and Roselli continued to see each other regularly. Piscopo, Bompensiero and Jimmy Fratianno all greatly admired Roselli.

Bompensiero told Piscopo that he had "handled some business for John" in Chicago going back to the 1940s. Roselli helped Bompensiero financially after he was released from prison in the 1960s. According to Piscopo, Roselli considered Bompensiero a "good man" and owed him "favors." Like Piscopo, Bompensiero would eventually betray Roselli to the FBI.

Piscopo said the Los Angeles Crime Family was relatively inactive and had only about twenty-five members. He identified them all to federal agents. [60] Nonetheless, the crime family remained a "tight, well disciplined, hardcore organization" that many individuals were "anxious" to join. Piscopo pointed out that many mobsters who were thought by law enforcement to be members were only associates. Those individuals included the Sica brothers, Alfonso Pizzichino and John Battaglia (brother of LCN member Charles Battaglia). [61]

Security Measures

Frank Desimone was "extremely surveillance conscious." He would routinely use "evasive and 'dusting off' techniques" to shake police tails. According to Piscopo, Desimone would spend long periods of time away from his home to avoid being subpoenaed. [62] Only his closest associates knew how to reach him when he took off. [63] (The FBI eventually determined Desimone was hiding at a friend's house in El Cajon, near San Diego.)

Valachi

After the publicity generated by Apalachin and Joseph Valachi's testimony at the McClellan Hearings in 1963, the Los Angeles Crime Family implemented security measures to minimize the risk from police surveillance. According to Piscopo, Desimone suspended all meetings between members. If members absolutely had to get together, a meeting had to be arranged at a racetrack, restaurant or a similar public place. Members were also told to avoid public gatherings like funerals and weddings. [64] (Frank Bompensiero told federal agents that to his knowledge that last meeting of the entire Los Angeles Crime Family together occurred in 1956.) [65]

Desimone ordered all telephone conversations between members to be kept to a minimum and that overall contact between members was to be "extremely limited." [66] All telephone calls had to be done using a public phone booth at prearranged times. To confuse anyone listening in, Desimone instructed them to speak in Italian using secret codes and to avoid using names and other specifics. [67]

Desimone feared law enforcement might secretly infiltrate the organization. Piscopo said Desimone would kill a member on the "slightest suspicion" that he was cooperating. [68] Nick Licata, though, was confident the organization could survive any attempts of "infiltration" by law enforcement. [69] He told Piscopo that "Our Thing will never be destroyed."

Discipline

A boss could suspend a soldier if he broke the rules. While suspended, the individual couldn't represent himself as an LCN member and couldn't participate in any criminal activity with other members. In Los Angeles, it was called being "read out" of the organization. It could last an indeterminate length of time.

According to Piscopo, Nick Licata was temporarily "read out" of the organization years ago for unknown reasons. Licata had to sever all contacts with organization including his criminal activities with other members. Piscopo said Licata always blamed Tom Dragna, the former consigliere, for his suspension. (This might explain why Dragna was exiled to Las Vegas after Licata became underboss under Frank Desimone in 1956.)

Costello

New York boss Frank Costello was another mobster who was "read out" of LCN for a time. [70] Costello and Vito Genovese had been longtime allies in what became the Genovese Crime Family. After Genovese fled the United States, Costello replaced him as boss of their crime family. Friction developed between the two men after Genovese returned to New York City and maneuvered to become boss again. According to Piscopo, the friction was exacerbated by the "machinations" of caporegime Anthony Strollo, who tried to manipulate the ill feeling between Costello and Genovese to further his own ambitions. Strollo hoped to pit them against each other and become boss himself.

In his attempt to take over again as boss, Genovese tried to kill Costello. Costello survived the assassination attempt but he handed power over to Genovese anyway. Instead of trying to finish off Costello, Genovese suspended him from the organization. Costello was forced to give up all his criminal interests and to have no more contact with other LCN members.

Soon afterwards, Costello and Genovese were both arrested and ended up being cellmates. According to Piscopo, Costello and Genovese "compared notes" and discovered Strollo had been pitting them against each other. Genovese reacted by lifting Costello's suspension and issuing a murder contract against Strollo. Strollo later disappeared. Piscopo said the "word passed to the Los Angeles Brugad by the New York group was that 'Strollo had been put in the press.'"

Head Tax

The Los Angeles Crime Family used to impose a "head tax" on its members to raise funds for the boss. (Other crime families had similar schemes.) Piscopo said the head tax was no longer collected but in the past, soldiers paid $10 per month while caporegimes paid up to $100 per month. [71]

The funds were supposed to be used to help pay the legal expenses of any member in trouble with the law or to help the family of an imprisoned member. However, in reality, the boss could use the funds any way he wanted and no one could say anything.

Extortion

Piscopo told federal agents that extortion was the backbone of the Los Angeles Crime Family. [72] The organization used violence or the threat of violence to collect money from anyone that could pay it.

Piscopo recounted how Desimone "borrowed" $10,000 from casino owner Nick Simponis. [73] Simponis was controlling partner in the Desert Sands Casino in Cabazon, California. Desimone used $4,000 to pay travel expenses connected to Commission meetings. $3,000 was set aside for the "kitty" to be used for future crime family activities, and the remainder was divided among Desimone, Licata and others associated with arranging the loan. Piscopo said no one in the crime family dared question how Desimone spent the money. Desimone never repaid the money.

Murder

Cohen

Piscopo said there were three main criminal groups active in Los Angeles during the 1940s and 50s. [74] Besides the Los Angeles Crime Family, there was a Jewish group led by Benny Siegel and Mickey Cohen, and a third group led by the Sica brothers. The brothers sometimes did strong-arm work for the Los Angeles Crime Family. Many in law enforcement thought they were LCN members but Piscopo indicated none of the brothers, in fact, were inducted (by 1963).

Conflict was commonplace in Los Angeles and would sometimes lead to murder. Jimmy Fratianno would write about a number of these murders years later in his memoir. What the public didn't know at the time was Piscopo had supplied details about many of the same murders in the early 1960s and the FBI had been sitting on the details for almost twenty years before Fratianno came clean.

Les Brunemann

(1937)

Les Brunemann was a prominent gambling figure in Los Angeles during the 1930s. According to Piscopo, Brunemann ran up against the Los Angeles Crime Family after he tried to expand his criminal activities into their territory. [75] Brunemann was shot and killed sitting in a cafe. At the time of his death, he was recovering from wounds sustained from another attempt to kill him a few months earlier. [76]

Los Angeles Times, Oct. 26, 1937.

Frank Niccoli and David Ogul

(September/October 1949)

According to Piscopo, David Ogul and Frank Niccoli, members of the Mickey Cohen group, were murdered at the instigation of the Los Angeles Crime Family for allegedly talking to law enforcement.

Piscopo said Frank Niccoli was killed in the home of Jimmy Fratianno in September, 1949. He said Fratianno and his associates disposed of the body and it was never found.

A month later, Ogul disappeared. Piscopo said that Ogul was beaten to death by associate Harold "Happy" Meltzer. Meltzer, an old narcotics trafficker and loanshark, had run afoul of LCN members for allegedly talking with law enforcement in New York City. To save his own skin, Meltzer agreed to betray his former friend to "square himself" with the Los Angeles Crime Family. [77]

According to Piscopo, Meltzer "delivered" Ogul's body to Dragna's men, "who buried him in a remote, rocky spot in the mountain area north of Los Angeles."

Happy Meltzer

In 1967, Piscopo said Harold "Happy" Meltzer was "the most active criminal figure in the Los Angeles area." [141] Meltzer "engaged in extensive shylocking and bookmaking activities." He shared the proceeds of these activities with Nick Licata. Piscopo suspected Tom Dragna or Louis Tom Dragna also profited from Meltzer's activities.

Samuel Rummel

(December 11, 1950)

Attorney Samuel Rummel, an associate of gangster Mickey Cohen, was shot in the back outside his home. Piscopo identified the shooter as Angelo Polizzi. He said the gun was supplied by Nick Licata from "an arsenal of such weapons maintained by the Los Angeles 'family' for such assignments."

Tony Trombino and Tony Broncato

(August 6, 1951)

L.A. Times

Aug. 7, 1951.

Trombino and Broncato were two smalltime criminals that robbed LCN-connected gambling operations. The Los Angeles Crime Family decided to do away with them and assigned the murder contract to Jimmy Fratianno. According to Piscopo, the actual triggerman were Fratianno and Charles Battaglia. [78] Piscopo was actually rounded up by police in the murder although he was later released.

Frank Borgia

(December 2, 1951)

Los Angeles Crime Family member Frank Borgia was killed on orders of Jack Dragna after he refused to give Dragna $25,000 from the sale of his winery. His body was never found. In the past, Borgia, a wealthy businessman, had supported the crime family financially and had always agreed to any request made by Dragna. Infuriated, Dragna accused Borgia of informing on the group and blamed his refusal to provide the money as proof of his disloyalty.

Borgia was "made" in the late 1940s. Piscopo indicated Borgia had been inducted into the crime family for the financial help he might give rather than for any criminal help he might provide.

Russian Louis Strauss

(April 16, 1953)

Louis Strauss was a hustler who allegedly tried to finagle money from gambling operator Benny Binnion by shooting his vehicle and blaming it on an imaginary crime group from Chicago. Binnion fell for the scam and began paying money to Strauss to settle the beef with Chicago. According to Piscopo, crime boss Jack Dragna found out about the scam and approached Binnion to take care of the problem. This way, Binnion would be in debt to Los Angeles.

According to Piscopo, Dragna assigned Jimmy Fratianno, Sam Bruno and possibly Joseph Dippolito to kill Strauss. They lured Strauss to his death with an offer to participate in a jewelry heist in Beverly Hills. His body was never found.

James Delmont

(June 4, 1960)

Mobster James Delmont was wanted by the Buffalo Crime Family for trying to kill one of its members. Delmont was tracked down to California. Piscopo said Buffalo boss Steven Magaddino reached out to Frank Desimone for his help to kill Delmont. The murder contract was arranged through Nick Licata and given to Angelo Polizzi. (Polizzi was born in Buffalo)

Piscopo told federal agents that he learned details directly from Angelo Polizzi. Piscopo said Polizzi, in discussing the murder, "had violated one of the firm rules of the La Cosa Nostra."

Ralph Genovese

Piscopo provided a detailed account of one murder that could not be verified. Ralph Genovese was said to be a cousin of New York crime boss Vito Genovese. According to Piscopo, Genovese had skimmed money from the Los Angeles Crime Family and then traded on his powerful cousin's name to protect himself from retribution.

The Los Angeles Crime Family complained to Vito Genovese who said he'd take care of it. Piscopo told agents that the New York crime boss had his cousin tied to a table and sawed to pieces. [79]

Frank Nitti and the Chicago Mob

Piscopo provided the backstory on the suicide of former Chicago Mob boss Frank Nitti. [80]

In 1943, Nitti along with Johnny Roselli, Paul Ricca, Charles Gioe, Frank Maritote and the other leaders of the Chicago Mob were sentenced to ten years in the federal penitentiary after being convicted of extortion.

Chicago Tribune, March 20, 1943.

The extortion scheme began in the 1930s when Willie Bioff took over as head of the International Alliance of Theatre and Stage Employees. [81] The union controlled movie projectionists, stagehands and ushers throughout the country. With the assistance of Frank Nitti and the Chicago Mob, Bioff was able to extort millions from theatre owners and the motion picture industry in exchange for labor peace. Piscopo had a peripheral role in the labor-racketeering scheme as a member of the union.

According to Piscopo, Willie Bioff was considered Nitti's "man." Bioff was the primary link between the extortionists and the Chicago Mob. Nitti put LCN member Nick "Nicky Dean" Circella on Bioff's payroll to keep an eye on him. Circella acted as a courier for the mob's share of the profits.

The scheme came crashing down in the early 1940s when federal authorities began an investigation and flipped some of Bioff's associates. According to Piscopo, Chicago boss Paul Ricca planned to kill Bioff because he was convinced Bioff was "weak" and would talk as well. Ricca also wanted to send a message to anyone else considering testifying against the mob.

According to Piscopo, Ricca called off the hit after Nitti persuaded him that Bioff would remain loyal. Nitti was on the hook when Bioff rolled over and became the key witness against the mob. Nitti, Ricca, Roselli and the others were all convicted.

Piscopo said Nick Circella's showgirl girlfriend was killed by the mob in a deliberate house fire as a warning to Circella to plead guilty to the charges and take the "fall" for the rest of them. Circella, who had gone on the lam to avoid arrest, got the message and quickly hurried back to Chicago and was convicted of extortion. After serving his prison sentence, he was deported back to Italy.

Nitti was the only mobster not to serve his prison sentence. Rather than go to jail, Nitti killed himself after the other mobsters turned on him. According to Piscopo, Ricca blamed Nitti for their predicament. If Nitti had agreed to kill Bioff, they would have never landed in prison. Piscopo said if Nitti hadn't killed himself, the mob would have done it for him.

After serving four years in the penitentiary, Ricca, Roselli and the rest were paroled in 1947. After the terms of their parole had expired, the mob tracked down Willie Bioff and killed him.

Decatur Herald

Aug. 22, 1954.

According to Piscopo, Roselli later became convinced that Frank "Diamond" Maritote, brother-in-law of the late Al Capone, and Charles "Cherry Nose" Gioe had cooperated with authorities while they were imprisoned. After discussing the matter with the Ricca and the other leaders, Maritote and Gioe were killed.

It's generally accepted that Nitti succeeded Al Capone as Chicago Mob boss. Piscopo's account of the extortion scheme and Frank Nitti's suicide makes clear that Paul Ricca was the actual boss. Piscopo's characterization of the Chicago hierarchy was likely accurate since the source of his information, Johnny Roselli, was in a position to know.

History

Piscopo shared some "ancient history" about the Los Angeles Crime Family. [82] Member-informants generally had no qualms about revealing this sort of information since there was little chance it could rebound on them or anyone else. The mostly non-actionable Intel would rarely lead to an arrest but allowed the FBI to place mobsters and events into historical context.

Ardizzone

Ardizzone

Joseph Ardizzone was boss of the Los Angeles Crime Family between the mid-1920s and the early 1930s. Ardizzone was a suspect in at least three murders and was a veteran of the "bootleg wars" in Los Angeles during Prohibition. According to Piscopo, Ardizzone was unpopular with some of the "younger and ambitious" members of the crime family and they eventually plotted to kill him.

In 1931, Ardizzone and a criminal associate named Jimmy Basile were targeted in a shooting by three assailants with sawed off shotguns. Basile died at the scene. Ardizzone was wounded and taken to a hospital, where another unsuccessful attempt was made on his life.

Piscopo said a truce was agreed upon between Ardizzone and the insurgents - Ardizzone retired from mob in exchange for his life. The insurgents later had second thoughts about Ardizonne holding up his end of the bargain and decided to kill him anyway. Soon afterward Ardizzone went missing. His body was never found.

Dragnas

Jack Dragna

Jack Dragna succeeded Ardizzone as boss. He made his brother Tom Dragna consigliere. They ruled the crime family for the next twenty-five years. Piscopo admired the brothers and described them as "ruthless, domineering and extremely ambitious." [83]

Los Angeles Crime Family was at its "greatest strength" during this period. It controlled much of the organized crime in the city. It was an "era marked by violence and numerous killings." Jack Dragna died in 1956 and was succeeded by Frank Desimone.

Frank Desimone

Frank Desimone was son of former boss Rosario Desimone. Through his father, Desimone had developed a number of "strong friendships in the organization." Piscopo said Desimone had a lot of things going for him that made him the best choice to replace Dragna. He was educated, had a clean record and had never been identified as a LCN member. [84] And because he was an attorney, Desimone was able to meet with anyone in the organization without drawing "undue attention." In the past, Desimone had legally represented mobsters like Frank Bompensiero and Johnny Roselli.

Desimone

The expectation was Desimone would be able to operate the crime family "more successfully with much less publicity" or "violence" than an out-an-out hoodlum like Dragna.

But things didn't go that way. Desimone's life was turned upside down almost immediately when it came out that he had attended the mob meeting at Apalachin in 1957. His low profile disappeared overnight. Desimone was publicly identified as a mob boss and he began to receive a constant police attention.

The fallout forced Desimone to shut down his law practice. His health declined and his eyesight began to fail. According to Piscopo, Desimone was so fearful of police surveillance that he refused to meet with other family members and instead, he gave all his orders through his underboss Nick Licata.

Anytime Desimone wanted to meet with Licata, he would send a message to him to meet "tonight" or "tomorrow." According to Piscopo, Licata would know "where and when" to meet Desimone based on previously arranged plans. [85] The meetings were usually out of town and they changed locations frequently.

Desimone's refusal to meet with anyone besides Licata generated criticism. Former Los Angeles Crime Family member Charles Battaglia argued caporegimes had a right to meet with their boss in person. He told Piscopo that it was highly unusual for a boss to only speak with the underboss. [86] Other crime families didn't do it that way.

According to Piscopo, Desimone's paranoia hindered the Los Angeles Crime Family's ability to make money. [87] Desimone ordered his men to avoid shakedowns, extortions or strong-arm activities that might draw the attention of law enforcement. If a member had an idea to make money, he first had to consult with underboss Nick Licata who then take the proposal to Desimone for his approval. According to Piscopo, Desimone would always reject it with the comment, "We can't make a move now — things are too hot." [88]

For example, Piscopo said certain members wanted to shake down local Jewish bookmakers. Desimone nixed the idea because he feared the bookmakers were all police informants and would roll over on them. He figured it would just result in more "heat" for them.

Desimone's passivity upset the younger element in the family who wanted better leadership. Piscopo said the next boss would have to be more active and be more committed to improving things for the members.

Apalachin NY Mafia convention

Apalachin

The Commission prohibited the killing of any prominent LCN member without its prior approval. According to Piscopo, the rule was put in place to create stability in the Italian underworld and to protect the bosses against insurgents inside their own crime families. In theory, the Commission severely punished those individuals who broke the rule.

Piscopo gave the example of the murders of former New York boss Vincent Mangano and his brother Philip. [89] The brothers were killed by their subordinate Albert Anastasia. Anastasia was called on the carpet by the Commission. He claimed self-defense. He agreed to comply with Commission rules in the future and no further action was taken against him. Anastasia broke his promise a few years later when he allegedly killed his underboss without approval.

According to Piscopo, the Commission bosses felt Anastasia was "power hungry" and would eventually kill each one of them if they didn't stop him. As a result, the Commission arranged his murder. Piscopo said the primary reason for the Apalachin meeting in 1957 was to explain Anastasia's murder to the other LCN bosses.

Commission Meetings

Piscopo said Frank Desimone regularly went "out East" to attend Commission meetings. [90] Desimone "represented" the other smaller crime families in the Western United States at these meetings. Because the Los Angeles Crime Family was small, Desimone didn't participate in the actual meetings but met with some of the bosses afterwards to receive instructions. [91] The Lucchese Crime Family represented the interests of the Los Angeles Crime Family to the other Commission bosses at these meetings.

After meeting with the bosses, Desimone would then report back to the other West Coast crime families and pass on any messages. [92] Piscopo said Desimone had periodic "meets" with San Francisco Crime Family boss James Lanza and San Jose Crime Family boss Joseph Cerrito. [93] Desimone also passed on instructions to "the boss in Texas." (Joseph Civello, the Dallas crime boss, was Desimone's cousin.) [94]

Because of infighting in the Bonanno Crime Family in 1964, Piscopo said Desimone had to attend six Commission meetings during the course of the past year. Desimone complained that these trips were expensive and cost him a great deal of money. He used money obtained from the shakedown of a casino owner to defray the costs. [95]

In early October, 1964, Piscopo learned that Joseph Bonanno and his entire crime family had been expelled from LCN. Piscopo didn't say why but other confidential sources had told the FBI that Bonanno had been accused of plotting to kill some of his Commission rivals. The Commission had ordered every other crime family in the United States to drop all contacts with the Bonanno Crime Family. The expulsion order was in effect as late as April, 1965. [96]

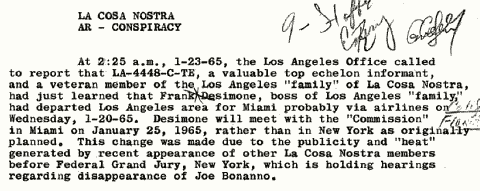

In January, 1965, Piscopo told federal agents that Desimone had recently gone to Miami to attend another Commission meeting. [97] The venue had been moved out of New York City because the bosses were afraid of being recognized and being subpoenaed to appear before a grand jury investigating the disappearance of Joseph Bonanno.

Piscopo wasn't sure what had been discussed at the meeting but he speculated that the Commission had appointed a new boss of the Bonanno Crime Family and that there would be a "re-recognition" of the Bonanno Crime Family by the other crime families. [98]

Licata Becomes Boss

Los Angeles Crime Family boss Frank Desimone died of natural causes on August 4, 1967. According to Piscopo, crime family members were instructed to avoid attending Desimone's wake and funeral, or send flowers. [99] This was in keeping with the general rule that Los Angeles Crime families members weren't to be seen in public with one another.

Licata

Piscopo told federal agents that underboss Nick Licata had assumed the position of acting boss until a new one was elected. [100] He didn't think Licata would get the position permanently since the new boss was usually promoted from the position of caporegime. [101] Piscopo added that many members felt "resentment" towards Licata for his lack of leadership. Nonetheless, he predicted Licata would still try to "line up" support to become boss. Caporegime Joseph Dippolito was another candidate for the top spot.

Piscopo explained how the election worked. Every family member had one vote. However, the most powerful members like the caporegimes had an outsized influence in the process and really decided who the next boss would be. Piscopo said caporegimes would normally consult with soldiers in their group, but in practice members ended up voting for the candidate backed by their caporegime.

Polizzi

Piscopo said Johnny Roselli could end up deciding who became boss. Even though he was a member of Chicago Crime Family, Roselli was widely respected in Los Angeles and would be consulted for his opinion. Piscopo's view was the candidate backed by Roselli would probably win out.

Piscopo said he consulted with Angelo Polizzi, his caporegime, before the election. Polizzi had recently suffered a stroke so Piscopo had to visit him in hospital. Polizzi asked Piscopo who he supported for boss. [102] Piscopo told Polizzi that his first choice was Nick Licata but he would support Polizzi if he wanted the position. Piscopo told Polizzi he would support whomever Polizzi recommended.

Polizzi stated that his first choice was Licata. Polizzi reasoned it was no time to make any dramatic changes. Polizzi told Piscopo that there was "no opposition to Licata" from the other caporegimes. Polizzi said he expected Licata would be the popular choice.

Brooklier

Piscopo reported back to federal agents that Licata would likely become the next boss. He had the support of Polizzi, the caporegime with the greatest number of soldiers, and he had the support of the caporegime in San Diego. Polling of the rest of the members, Piscopo added, would be a "mere formality." [103]

In October, 1967, Piscopo advised federal agents that Licata had been elected boss. In addition, former caporegime Joseph Dippolito had been elevated to the position of underboss. Dominick Brooklier, formerly a soldier in Dippolito's crew, was appointed to replace him. [104] Licata would oversee the Los Angeles Crime Family until his death in 1974.

(Los Angeles Crime Family member Frank Bompensiero gave a slightly different explanation of how the boss was chosen. By 1967, Bompensiero had begun to cooperate and he was much more active and well-informed about goings-on in the crime family than Piscopo. He said the Commission directly advised the administration in Los Angeles to hold a meeting and select a new boss. After a new boss was selected, every member of the crime family was to be "polled individually to see if they concurred with this decision.") [105]

Nick Simponis

Nick Simponis was a close associate of Salvatore Piscopo. He controlled the Desert Sands Casino in Cabazon, California. The casino was a great moneymaker for the crime family.

Limandri

Piscopo said Simponis had gained controlling interest in the Desert Sands by secretly accumulating ownership points behind the backs of the original owners. [106] After the original owners figured out that they had been had by Simponis, they turned to LCN members Gaspare Matranga, Joseph Limandri and his brother-in-law Joseph Dippolito for help to regain control of the casino. They began to make trouble for Simponis.

In order to protect himself, Simponis turned to Nick Licata and Joseph Giammona for support. This meeting was likely arranged by Piscopo. [107] For a secret thirty percent ownership stake in the casino, Licata told Limandri and Dippolito to back off. It's unclear if Matranga, Limandri and Dippolito were aware of the secret backroom deal made with Licata.

According to Piscopo, Simponis delivered about $5,000 to Piscopo every month to handover to Licata. In addition, twice a year Simponis gave a bonus of $50,000. to Licata. Piscopo eventually passed on the collection duties to Frank Stellino, the son-in-law of Nick Licata and the nephew of Dominic Brooklier. [108]

Stellino

Frank Bompensiero told Piscopo in 1965 that he intended to shake down Nick Simponis if he got the approval of Johnny Roselli and Frank Desimone. [109] Bompensiero may not have been fully aware of the entanglements between Simponis and the Los Angeles Crime Family, and that Simponis was under Licata's protection.

In 1966, the Los Angeles Crime Family sold their secret thirty percent ownership stake in the casino back to Simponis for $50,000.00. [110] According to Piscopo, Licata believed the casino was poorly operated and "had not realized its full potential." [111]

But the crime family regretted the sale almost immediately. Simponis subsequently built a new luxurious casino in Cabazon. [112] According to Piscopo, Simponis used his political influence over the Cabazon city council to obtain exclusive gambling rights and keep out the competition.

After Licata became boss in 1967, he tried "cutting into" Simponis' casino operations again. According to Frank Bompensiero, the Los Angeles Crime Family "attempted to muscle their way back in" but backed off after "Simponis began to 'scream' and threatened to go to the FBI…" [113]

In 1968, a new city council was elected and it gave permission for another casino to operate. The new gambling venture was to use the same building that once housed Simponis' old casino. Simponis told Piscopo that he was extremely concerned the new casino would eat into his profits.

According to Bompensiero, Simponis was going to restart paying Nick Licata a monthly tax to operate his casino. [114]

Johnny Roselli

Johnny Roselli

Johnny Roselli had been in the crosshairs of law enforcement for years. After Roselli was convicted of extortion in 1943, federal authorities began to take a closer look at him and his background. They came away convinced Roselli was using a fake name and was in the United States illegally. If federal authorities could prove that Roselli was born in Italy, they could deport him and have one less mobster to worry about. But they needed proof.

Piscopo had known all about Roselli's true identity since the 1920s but he had always protected him when questioned. For example, in 1954, the Immigration and Naturalization Services interviewed Piscopo about his relationship with Roselli. He told investigators that they were distant cousins, which was a lie. [115] He said he only met Roselli in 1930 and knew nothing about his early life. As far as he knew, Roselli was born in San Francisco or Chicago. These lies were started by Roselli years earlier to give credence to his made up background.

Even after he began to give up information on his associates in 1963, Piscopo continued to lie on Roselli's behalf. He gave up more information about Roselli than he had in the past but he still protected his false identity. For example, in May, 1963, Piscopo told federal agents that he had known Roselli since 1923. [116] He said both their families came from Caserta, Italy. He said he believed Roselli was born in Chicago. He said he met Roselli through Roselli's alleged uncle, Anthony D'Acunto. As far as he knew, Roselli's real name was "Roselli." He said Roselli first came to California as a child to alleviate his tuberculosis. Roselli told Piscopo the warm weather saved his life.

Piscopo finally gave up everything he knew about Roselli on March 4, 1964. [117] Piscopo was spotted in Los Angeles meeting secretly with an individual by the name of Albert Sacco from Boston. [118] The FBI had no idea who Sacco was and were very suspicious that Piscopo had hidden the meeting from them.

Confronted by the FBI, Piscopo cracked and admitted that Sacco was the brother of Johnny Roselli. Piscopo told federal agents that Roselli's real name was Filippo Sacco and that he was born in Caserta, Italy. He said Roselli was brought to the United States as a child.

Piscopo said he met Roselli for the first time in the 1920s in Los Angeles and that he was already using the name Roselli. They became criminal associates and eventually close friends. He said it was during these early days that Roselli shared details of his birth and early life with him. [119] Piscopo admitted that he had been secretly couriering money to Roselli's family in Boston for years.

Piscopo said Roselli was a member of the Chicago Crime Family. He described Roselli as "one of the most powerful and influential men in LCN." [120] Roselli was "highly respected and frequently consulted relative to and handles matters of highest importance and greatest delicacy."

The FBI sat on the information for two years before they approached Roselli. The Bureau first wanted to complete an investigation into Roselli's background without alerting him and it wanted to make sure none of this came back on Piscopo. [121]

Young Roselli

The FBI finally confronted Roselli in May 1966. The Bureau tried to get Roselli to cooperate against the mob to avoid deportation but he refused.

In a face-to-face meeting on May 17, 1966, Piscopo told Roselli that he had recently been interviewed by federal agents about Roselli's true identity. [122] Roselli had no idea yet that Piscopo was the man who betrayed him. Piscopo denied any involvement in revealing his true identity.

Roselli told Piscopo he wasn't worried that federal authorities had figured out his real name. He was more concerned new information might emerge about his violent past. Roselli implied that under his real name of "Sacco," the FBI would find information linking him to a "shooting."

Roselli said there were five individuals from his past who could sink him with dirt. He didn't identify them by name but he said three lived in New York, one lived in Boston and one was in Italy. Piscopo said the individual in Italy was Tancredi Tortora. Piscopo said Tortora and Roselli were arrested together in the 1920s on a narcotics charge.

According to Piscopo, Roselli was later able to destroy the police mugshot from the narcotics bust. Piscopo said Roselli and Tortora may have also been involved in the murder of Chicago mobster Tony Charlando in the 1920s. Tortora was later convicted for another murder and was later deported to Italy. [123]

Piscopo said that he received a letter many years later, in his capacity as Roselli's "secretary," from Tortora addressed to Roselli demanding money. Roselli ignored the letter and refused to send any money. Roselli told Piscopo that he had heard Tortora had "done a little talking" in the past and was worried he might reveal more incriminating information about him. [124] The FBI would later interview Tortora based on Piscopo's Intel. Tortora would provide investigators with valuable information about Roselli's early years.

Exposed

As early as May, 1968, the Los Angeles Crime Family was aware that Piscopo was talking with the FBI. [125] An unidentified informant, likely longtime mobster Harold "Happy" Meltzer, told his own FBI contacting agent that he had been personally warned by Nick Licata to "stay away from and not have anything to do with [Piscopo] because this individual ... was an informant for the FBI." [126]

Licata didn't reveal to Meltzer how he discovered Piscopo was an informer but his source was likely Johnny Roselli. After Roselli learned in 1966 that the FBI knew all about his true identity, he asked former FBI agent Ed Morgan to find out who ratted him out. Roselli was shocked to discover his old friend Piscopo had spilled the beans. [127] Piscopo had only just told Roselli to his face that it wasn't him.

Because it was unlikely that Licata would tell an associate like Meltzer before telling inducted members of the crime family, by this time news of Piscopo's cooperation almost certainly had been circulated among LCN members. [128]

Meltzer

Roselli's first instinct was to kill Piscopo. Roselli allegedly received permission from his superior, Chicago boss Sam Giancana, to contact Piscopo's boss Frank Desimone and demand he whack him. Ordinarily, this should have been a straight forward request. LCN members were forbidden from talking to law enforcement under pain of death. In fact, Desimone had indicated in the past that he wouldn't hesitate to kill a member who turned out to be a rat. But Desimone refused to give the go ahead.

According to All American Mafioso, Desimone was jealous of Roselli's underworld reputation and had never forgiven him for transferring his membership to the Chicago Crime Family in 1957. [129] Fratianno said he felt Piscopo was too rich and too connected with Desimone and Licata to be killed. [130] Whatever the true reason, Roselli had to live with the decision because Piscopo was a Los Angeles Crime Family member and he was untouchable to outsiders.

But that scenario is hard to reconcile with Piscopo's subsequent behavior. For example, if the Los Angeles Crime Family knew Piscopo was an informant in 1966, why did it allow him to meet freely with other crime family members and participate in the election of a new boss in 1967? [131] Even if the powers that be decided he wasn't worth killing, it seems beyond belief that they would allow him to remain a member in good standing.

The publicly available FBI documents linked to Piscopo, which largely dry up after 1967, don't indicate how federal agents managed to protect him after it came out that he was a confidential informant or how they managed to act on the information without exposing Meltzer as the source. He was helping the FBI as late as 1969. [132]

All indications are Piscopo remained in Los Angeles despite the rumors he was an informant.

This suggests Piscopo had some sort of rapprochement with Licata and the Los Angeles Crime Family. Perhaps Piscopo was read out of the organization as punishment.

According to Jimmy Fratianno, Piscopo ended his days blind and alone. [133] His wife had died years earlier. Piscopo died of natural causes on December 6, 1977, in Los Angeles County. [134] He was a few days shy of turning age 84.

Notes

1 FBI documents are full of information supplied by multiple sources hidden behind informant symbol codes. This anonymity makes it difficult to ascertain how much weight to give certain disclosures over others. Is the source a low-level associate or is he an inducted LCN member close to the boss? There is great value in being able to isolate what a mobster like Piscopo told the FBI.

2 Manifest of aliens employed on S.S. Regina d'Italia as members of crew, departed Naples on Dec. 21, 1920, arrived New York City on Jan. 6, 1921, Familysearch.org. The name and birthplace are matches for Piscopo, but the birth year is off by one year.

3 Naturalization Index, United States District Court for the Southern District of California (Central) at Los Angeles, certificate no. 4418085, petition no. 57656, April 22, 1938, Familysearch.org.

4 Salvatore Piscopo World War II Draft Registration Card, serial no. U3297, Board No. 238, Los Angeles County, California, April 1942, Familysearch.org.

5 United States Census of 1920, New York State, Kings County, Borough of Brooklyn, Assembly District 13, Enumeration District 778, Familysearch.org.

6 New York City Marriage Records, July 10, 1922, Familysearch.org.

7 FBI, John Roselli, Legat, Rome, Aug. 31, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10291-10052.

8 United States Census of 1930, California, Los Angeles County, Los Angeles City, Assembly District 57, Enumeration District 110, Familysearch.org

9 Marriage License, County of Los Angeles, California, book 1249, page 298, license no. 15211, Oct. 15, 1934, Familysearch.org

10 Was the 1922 marriage to Gann invalidated (if it was) because Piscopo was still married to his first wife in Italy?

11 Passenger manifest of S.S. Conte di Savoia, departed Naples on April 3, 1935, arrived New York City on April 11, 1935, Familysearch.org

12 The fact his second marriage ceremony took place in 1934 and his daughter came to live with him soon afterward suggests his first wife may have died just before then.

13 George Piscopo Certificate of Birth, California State Board of Health Bureau of Vital Statistics, County of Los Angeles, Local Registered No. 7808, May 25, 1924, Familysearch.org; William George Piscopo Certificate of Birth, California Department of Public Health Vital Statistics, County of Los Angeles, Local Registered No. 7808, May 25, 1924, Familysearch.org. The original birth certificate was issued in the name of "George Piscopo" before it was amended to "William George Piscopo." George was the name of Evelyn Gann's brother.

14 FBI, John Roselli, Legat, Rome, Aug. 31, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10291-10052.

15 Evelyn Helen Piscopo Certificate of Birth, California Department of Public Health Vital Statistics, County of Los Angeles, Local Registered No. 10732, July 29, 1928, Familysearch.org. Helen was the name of Evelyn Gann's sister.

16 "Mass planned for victim of jet crack-up," Los Angeles Times, Nov. 7, 1950, p. 10; Daily Trojan, Vol. 42, No. 37, Nov. 07, 1950.

17 "Lieut William G. Piscopo," Find A Grave, Memorial no. 39992374, July 28, 2009, Findagrave.com.

18 "Evelyn D. Piscopo," Find A Grave, Memorial no. 66541119, March 5, 2011, Findagrave.com.

19 United States Census of 1940, California, Los Angeles County, Los Angeles City, Enumeration District 60-195, Familysearch.org.

20 FBI, John Roselli, Los Angeles Office, March 15, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10287-10336.

21 FBI, John Roselli, Los Angeles Office, Aug. 30, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10288-10209.

22 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 11, 1929; FBI, John Roselli, Legat, Rome, Aug. 31, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10291-10052, pp. 5-6. The age of the Piscopo in this newspaper account is inconsistent with the Salvatore Piscopo from Los Angeles. Also, it's unclear why Piscopo, a Los Angeles-resident, would have a New York City address.

23 FBI, John Roselli, Legat, Rome, Aug. 31, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10291-10052.

24 FBI, John Roselli, Legat, Rome, Aug. 31, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10291-10052.

25 Evelyn Helen Piscopo Certificate of Birth, Familysearch.org.

26 United States Census of 1940, Familysearch.org

27 Marriage License, County of Los Angeles, Familysearch.org.

28 Salvatore Piscopo World War II Draft Registration Card, Familysearch.org.

29 FBI, John Roselli, Los Angles Office, June 18, 1962, NARA Record No. 124-10353-10355.

30 FBI, John Roselli, Los Angeles Office, Dec. 23, 1957, NARA Record No. 124-10200-10419.

31 Brooklyn Eagle, Feb. 7, 1950.

32 Cohen, Mickey as told to John Peer Nugent, Mickey Cohen: In My Own Words, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1975, pp. 36-39.

33 FBI, The Criminal "Commission," Los Angeles Office, Dec. 21, 1962, NARA Record No. 124-10216-10237. Simponis may have begun to share some information after the mob muscled into his gambling operation.

34 FBI, La Causa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, June 6, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10200-10446. "The Los Angeles Division, in its efforts to penetrate La Causa Nostra, previously advised that a live source LA 4412-C-TE, was in close daily contact with Salvatore Louis Piscopo, who apparently was a member of this organized group. As a result of information furnished by LA 4412-C-TE, investigation went forward toward the further penetration of this organization and certain interviews were conducted on 4/29/63 and 5/2/63, which, in turn led to the eventual development of LA 4448-PC..."

35 FBI, The Criminal "Commission," Los Angeles Office, Dec. 21, 1962, NARA Record No. 124-10216-10237. Simponis told federal agents that Piscopo was part of a New York crime family but there is no evidence that was true.

36 FBI, Frank Sinatra, Los Angeles Office, Feb. 8, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10352-10012. Piscopo was referred to as "Merli" in the transcript.

37 Rappleye, Charles & Becker, Ed, All American Mafioso: The Johnny Roselli Story, New York: Barricade Books Inc., 1995, p. 260.

38 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, July 22, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10208-10406.

39 FBI, La Causa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, June 6, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10200-10446; FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, July 22, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10208-10406.

40 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, May 12, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10204-10433.

41 FBI, La Causa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, June 6, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10200-10446.

42 Nolan, William John, "La Causa Nostra," FBI report of Los Angeles office, file no. 92-6054-289, NARA no. 124-10200-10446, June 6, 1963, p. 3; "Dragna morals charge heard," Los Angeles Times, June 21, 1951, p. 15; "L.A. cop's 'hearing' told in Dragna trial," Los Angeles Mirror, June 21, 1951, p. 28; "Hint wiretap defense for Dragna," Los Angeles Daily News, June 25, 1951, p. 30; "Jack Dragna released on bail," Santa Maria CA Times, July 27, 1951, p. 5; "Jack Dragna says police tricked him," Hollywood Citizen News, June 14, 1952, p. 3; "Annette Eckhardt and Jack Dragna," photograph from Los Angeles Herald Examiner issues of June and July, 1951, Herald Examiner Collection, Tessa, Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

43 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Sept. 4, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10328.

44 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Dec. 13, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10206-10413.

45 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, July 22, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10208-10406.

46 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, Oct. 20, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10277-10308.

47 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, July 22, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10208-10406.

48 FBI, La Causa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, June 6, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10200-10446; FBI, Top Echelon Criminal Informant Program, Los Angeles Office, Jan. 13, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-90133-10224. Piscopo let federal agents know when out-of-town mobsters like Frank Scibelli and Sam Cufari visited California.

49 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Phoenix Office, July 20, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10223-10466. Piscopo was the first member-informant to confirm the existence of an active LCN group in Tucson.

50 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, May 12, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10204-10433.

51 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Dec. 13, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10206-10413.

52 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, July 22, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10208-10406.

53 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Oct. 4, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10293. Joseph Giammona joined the crew after he was busted down from caporegime; FBI, La Causa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, June 6, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10200-10446.

54 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, San Diego Office, Nov. 24, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10289-10201.

55 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Aug. 20, 1968, NARA Record No. 124-10297-10113.

56 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Dec. 13, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10206-10413.

57 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, July 22, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10208-10406.

58 FBI, La Causa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, June 6, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10200-10446.

59 FBI, John Roselli, Los Angeles Office, Nov. 26, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10291-10055.

60 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, Oct. 20, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10277-10308.

61 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Dec. 13, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10206-10413.

62 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Dec. 13, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10206-10413. Caporegime Angelo Polizzi also regularly hid out to avoid being subpoenaed.

63 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Jan. 15, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10223-10362.

64 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, July 22, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10208-10406.

65 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, San Diego Office, March 13, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10222-10055.

66 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, Jan. 29, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10206-10406; FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Sept. 4, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10328.

67 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, July 22, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10208-10406.

68 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, July 22, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10208-10406.

69 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Jan. 15, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10223-10362.

70 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Dec. 13, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10206-10413.

71 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, July 22, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10208-10406.

72 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Sept. 4, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10328.

73 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Dec. 13, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10206-10413.

74 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Dec. 13, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10206-10413.

75 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, July 22, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10208-10406.

76 In his memoir, Jimmy Fratianno identified the shooters as Leo Moceri and Frank Bompensiero. Career criminal Peter Pianezzi was framed for the murder and spent thirteen years in prison. Pianezzi was given a full pardon in 1981 based partly on Fratianno's information. In 1966, Pianezzi rejected a less comprehensive pardon called a "pardon through rehabilitation." This offer was made only a few years after Piscopo gave evidence that Pianezzi was innocent.

77 Demaris, Ovid, The Last Mafioso: The Treacherous World of Jimmy Fratianno, New York: Times Books, 1981, p. 35.

78 Albany Times Union, Aug. 12, 1951. Piscopo was wanted by police for questioning in the murder of Trombino and Broncato. Although he wasn't considered a suspect, police described Piscopo as a "muscle man" who was "hooked up with the men." Police believed Piscopo could tell them "plenty" about Jimmy Fratianno, the prime suspect in the murder.

79 There is no independent corroboration of this murder.

80 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, July 22, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10208-10406.

81 FBI, The Criminal "Commission," Los Angeles Office, Dec. 21, 1962, NARA Record No. 124-10216-10237. Simponis stated that Piscopo said he was brought to Los Angeles "by Johnny Roselli to participate with Roselli and Willie Bioff in the old theatrical union wherein Roselli and Bioff were convicted for shaking down the movie industry."; FBI, Johnny Roselli, Los Angeles Office, June 18, 1962, NARA Record No. 124-10219-10259.

82 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, July 22, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10208-10406.

83 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, July 22, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10208-10406.

84 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, July 22, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10208-10406.

85 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, May 12, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10204-10433.

86 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Sept. 4, 1967, NARA Record No.124-10293-10328.

87 Not only did Desimone have to worry about law enforcement taking him down, New York boss Joseph Bonanno had tried to eliminate him in a coup attempt in the early 1960s. According to one source, Bonanno secretly tried to get Frank Bompensiero to kill Desimone. Bonanno reportedly hoped to put his son in the top spot. The plot was foiled after Desimone found out about it and complained to the Commission.

88 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Sept. 4, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10328.

89 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Dec. 13, 1963, NARA Record No 124-10206-10413.

90 FBI, Joseph Francis Civello, Dallas Office, Feb. 9, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10298-10043.

91 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Sept. 4, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10328.

92 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Jan. 13, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10223-10351.

93 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, May 12, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10204-10433.

94 FBI, Joseph Francis Civello, Dallas Office, Aug. 26, 1968, NARA Record No. 124-10288-10418. Besides Joseph Civello, Piscopo identified Joseph Ianni and Johnny Patrono as Dallas LCN members.

95 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Dec. 13, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10206-10413.

96 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, May 12, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10204-10433.

97 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, J.H. Gale to Mr. Belmont, Jan. 23, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10223-10366.

98 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Jan. 15, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10223-10362.

99 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Sept. 4, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10328.

100 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Aug. 20, 1968, NARA Record No. 124-10297-10113.

101 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Sept. 4, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10328.

102 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Oct. 4, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10293.

103 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Oct. 4, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10293.

104 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Aug. 20, 1968, NARA Record No. 124-10297-10113.

105 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, Oct. 20, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10277-10308.

106 FBI, La Causa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, June 6, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10200-10446.

107 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, July 1, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10278-10231. The "third party" was likely Piscopo.

108 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, July 1, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10337-10014. Some of this money was forwarded to mob interests in New York City.